It was Dr Greg Hillis who in 2016 asked me to give the Fr Vernon Robertson Lecture, at Bellarmine University. Greg very much wanted me to address the topic of immigration, and I was happy to do so.

I traveled to Ballarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky, on 28 March, 2017, to give a lecture entitled “The Politics of Human Dignity: Catholics and Immigration” .

While I was in Louisville, Greg showed me the University, took me to visit Gethsemani Abbey. He delighted in showing me around, introducing me to the monks and sharing with me the stories about Thomas Merton’s hermitage on the grounds of the Abbey. We communicated regularly thereafter. Greg passed away in 2024 after a heroic battle against cancer. I reflect often on the generous time and hospitality he gave to me on my visit. And I am grateful to God for his example as a theologian and “man of the Church” (to use de Lubac’s phrase). May he rest in peace.

Here below is the text of the lecture I gave on the occasion of that 2017 visit. I think it remains relevant to our current situation.

+dflores

The Politics of Human Dignity: Catholics and Immigration (2017)

The topic of this lecture is Catholics and the issue of immigration. I view this lecture as mostly addressed to how Catholics can properly grapple with this issue. Catholics have a responsibility to enter into the discussion about immigration in a serious way, and we have a decisive mission to sanctify the discourse that permeates the political process. My lecture today, though, in no way takes for granted that most Catholics are in fact engaged in the discussion, as Catholics. That is to say as equipped to purify, elevate and thus sanctify the situation we face. I rather think many are not. We have far to go. Yet it seems to me Bellarmine University is a good place to lend a bit of shoulder to the effort.

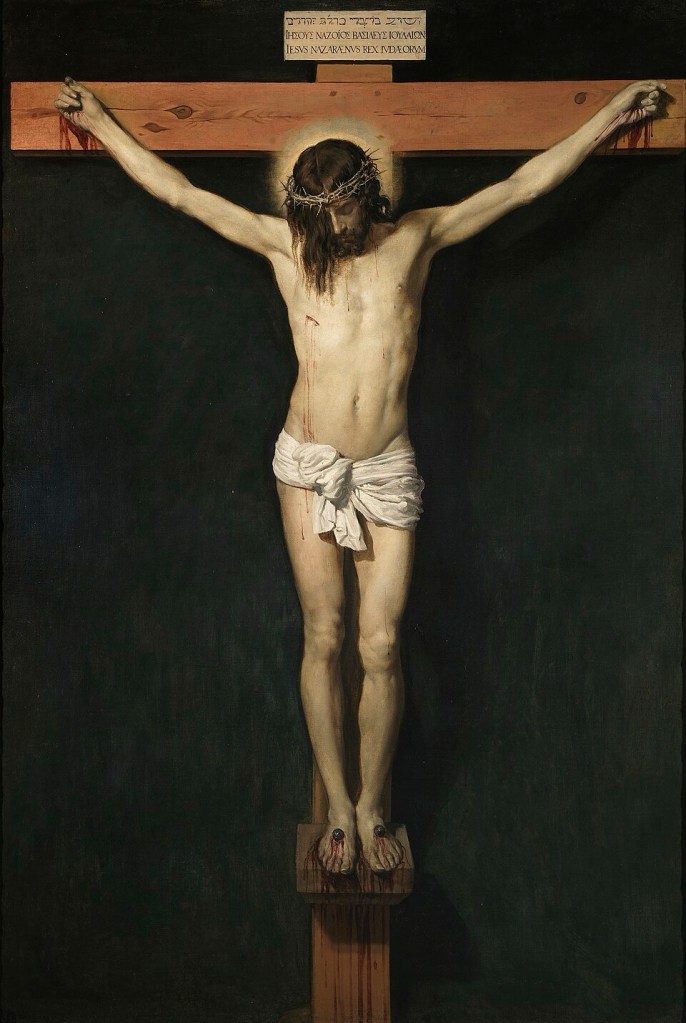

I begin, though, with a verse written by the 20th Century Spanish essayist and poet Miguel de Unamuno who gave to us a poetic meditation on Christ Crucified, emerging from his contemplation of the Crucified painted by the 16th Century artist Diego Velázquez. The poet converses with the artist and his work, exemplifying thereby a rich dialogical tradition of image and word. The translation, for better or for worse, is my own:

While the earth in loneliness sleeps,

there watches the white moon; the Man watches

from his Cross, while men sleep;

watches now the man without blood, the Man white

like the moon of the black night;

watches now the Man that gave all his blood

that the peoples might know that they are men. (1)

A Catholic must begin with hope which for us can only emerge from our contemplation of the One who watches in the night. For us politics can only really be about keeping faith with Him, and what he shows us about God, about ourselves and about our neighbor. For He comes, “that the peoples might know that they are men”.

+++

I am not primarily interested in talking about the current state of political discourse in the United States. I will, however, have to do so in order to clarify in some way how a Catholic moral and political perspective differs from the current dominant way of talking about this issue. So, I will spend a few lines on a description of the current political and moral universe Catholics inhabit.

The state of public discourse about immigration and immigrants is an exemplary case of a poverty that exists within our culture. By poverty I mean that the culture seems to lack the resources needed to engage in significant moral discourse on issues that impact the social order. We churn like a perpetually stationary hurricane sitting in the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. Immigration is not the only exemplary case, there are others. Still, it is the one I want to address today.

We are mired in a poverty of moral discourse that manifests itself principally as an perpetual battle of narratives. And this happens in two ways: first the narratives are presented more or less syllogistically, and second, the place of sentiment and emotion in the narrative is used to bolster the persuasive intent of the narrative. Classically, persuasion is aimed at the will, though in modern political discourse this is so only confusedly. The discourse is not primarily aimed at the will as the agent of rational judgment about what is best to do about immigration, but rather at the will insofar as it can be moved by sentiment to accept a narrative syllogism, from which follows a position on immigration. The narratives in themselves are problematic inasmuch as they are mutually exclusive, but what is more corrosive is the manner in which the narratives are evaluated.

The first problem here is the widespread belief that the battle is won by those who are perceived to have the most relevant facts on their side. And despite the fact that these facts are passionately and often angrily listed, all sides in the debate seem to accept as given that facts are facts and that their moral import follows as an evident conclusion upon the narration of them.

The role of the emotions in this dynamic is inordinate precisely because they are asked to bear the decisive weight. Since the syllogistic narratives evidently fail to persuade a majority one way or the other, as a practical matter, the extra push to political judgment is supplied by appeal to emotion and sentiment. Each side will ascribe to itself the appropriate sentiment motivating its own narrative of the facts. Proper love of country, respect for law and order, sympathy for national sovereignty are principally appealed to, while conversely, on the other side, the appeal is to global solidarity, concern for the poor, and compassion for the suffering of others.

These descriptions are usually coupled with a twin argument about the faulty sentiments of those in opposition. So the argument becomes one between sides that claim the moral evaluation of the other is faulty because of its corrosive relation to an inappropriate sentiment. Thus, for example, those sincerely in favor of a more humane immigration policy in this country often narrate the relevant facts and then discuss how the facts of those opposed are corrupted by anger, racism, hyper-nationalism etc. On the other side, those in favor of a stricter immigration policy, of walls and even mass deportations, list the facts relevant to them, and then charge the other side with an anemic love of country, of heartlessness in the face of crimes committed by immigrants, or of exaggerated sentiments of compassion for persons that this country is not able to help.

Thus, I suggest that the factual presentation is a competitive one, presented as exclusive of the other; the emotional narrative is also mostly a competitive one, exclusive of the other. To close the description here, the opposing sides tend to view each other’s facts and sentiments dismissively, and as irrelevant. Charges of irrelevancy further impoverish the discussion.

What is lacking in the discourse I have only briefly and generally described is a proper estimation of what constitutes a moral and political judgment. We never move to the discussion of how to integrate and prioritize the legitimate goods variously identified by both sides. Nor do we acknowledge that affections, despite their immediacy, are not beyond the need for purification. Without these steps, there is no real political judgment. This kind of atrophied discourse is a kind of poverty and paralysis in our culture, and not one that we need accept with resignation. Perhaps, as Thomas Pfau suggests in a very fine book called “Minding the Modern” the very concept of judgment as something involving a reasonable dialogical engagement with various goods and affections has slipped from our practical public awareness. (2) I will say more about this further step needed, in course.

+++

At this juncture, I would like to place on the table a few words about the broader Catholic moral imagination. An aspect of our contemporary Catholic culture is the increasing difficulty we have picturing how providence manifests itself. I do not mean giving a theological account of God’s governance, I mean shedding a little light on how everyday Catholics live and pray it. God’s governance in history expresses itself primarily through human agency. This is for a Catholic something so deep in our theological tradition and in our habitual awareness that in a memory-blocked age we can forget where it comes from.

I had it taught to me by my Grandmother, who used to rise early in the morning to pray several Rosaries. And when I would ask her what she prayed for, she would tell me that she prayed for all her grandchildren, especially the ones far away. She said simply that she prayed that if ever they are in trouble, God would put a kind and generous soul in their path to help them. She was a realist, that is to say, she knew her grandchildren, my older cousins, were quite capable of finding all sorts of trouble. But she was a woman of faith, and trusted to God that He would find ways to help them. Mostly, that meant He would put the right people in their path. The mirror image of that kind of perception, available to anyone with faith and a little imagination, is that we are also all potential answers to some grandmother’s prayer in some place far away. Indeed, the generosity God inspires in each one of us today is his answer to someone’s prayer.

This imaginative perception communicated to me by my grandmother is an echo of the lived transmission of the faith, and of many a hagiographical account. Perhaps most famously in the tradition is the account of Saint Francis and his encounter with the Leper. Surely the Leper prayed for a touch of human compassion, and surely God inspired something in Francis to respond in the way he did. (3) But Francis also prayed to know Christ most intimately, and in the Leper found Christ waiting. This awareness is present also in the stories told today among immigrants of the mysterious figure of Santo Toribio Romo, who is said to emerge from the desert to assist an immigrant who has lost his way and is in danger of perishing.

The daily perceptions of providence exist principally within the ethos of charity; that is to say, within an imaginative vision of life that sees cohesion in the grace God gives to a generous human heart, and the care for those who are in trouble. Even in a wounded world, people find themselves crossing paths with someone who will not abandon them to disaster. The parable of the Good Samaritan is prototypical of this perspective maintained in faith.

One could imagine the Father of the prodigal son praying in the way my Grandmother described, asking that someone be placed in his son’s life to render him aid in the moment of need. It is doubtful that the older brother bothered to pray this way, and indeed, the older brother’s unwillingness to go seek his younger brother is one of the “indictments by absence” present in the parable. I say this because a Christological reading of the parable takes note of how it begs for the sending of the “first born” to the aid of the younger sibling.

+++

Unamuno on Christ the reckoning rod and carpenter’s square:

You are the Man, the Reason, the Norm,

your cross is our reckoning rod, the measure

of the pain that elevates, and the carpenter’s square

of our rectitude: it makes straight

the heart of man when bowed low.

You have humanized the universe, O Christ.

«Behold the Man!» through whom God becomes something. (4)

I actually think most Catholics still perceive to some degree this mysterious dynamic linking human responses to divine governance. What is lacking, however, is a bridge between this manner of perceiving life and Catholic participation in contemporary discussions about a just social order. We are not sufficiently aware of the absence of this bridge, nor have we examined how it might be built. In this sense, I read the following passage from Pope Benedict’s Caritas in Veritate as a plea for the building of this bridge:

«The more we strive to secure a common good corresponding to the real needs of our neighbors, the more effectively we love them. Every Christian is called to practice this charity, in a manner corresponding to his vocation and according to the degree of influence he wields in the pólis. This is the institutional path — we might also call it the political path — of charity, no less excellent and effective than the kind of charity which encounters the neighbor directly, outside the institutional mediation of the pólis.» (5)

The political world Catholics inhabit seems to have no room for this kind of perspective. I do not mean simply a perspective that includes grace as a vehicle of human participation in the providence of a Good God, or a perspective that has room for the appearance of the miraculous in history; rather more to the point, I mean that the political discourse does not take sufficient account of human agency as intimately involved in the sustenance of human and social cohesion. Charity has been privatized, and as a result, our pursuit of adequately just solutions to contingent social circumstances has become truncated. Further, moral judgment, as an act of prudential reason, has also been privatized, and this has impact on the character of political judgment in the wider public sphere.

Part of the problem is that individual’s relations to the world outside are increasingly difficult to account for, apart from willing them. Our wider culture has no basis to talk about mutual concern and compassion apart from the language of purely willed associations. (6) These willed associations resolve to the isolated individual who tends to view relations suspiciously. When social relations are conceived as fundamentally voluntary, they are subject to severance for whatever provocation an encounter might unpleasantly cause. The “I do not want to deal with you” that is an ever present temptation to fallen nature becomes a normative and politically acceptable response.

Catholic moral teaching, including the Social Justice magisterium, presumes a metaphysics of human nature in relation, and proposes a healing and strengthening of these relations by faith, hope, and charity. The Church stubbornly insists that human political judgment cannot prescind from a metaphysically prior existential relatedness. When there is no intellectual respect within public discourse for the given of human relatedness, we end up with what Pope Francis calls the culture of indifference. Indifference perceives no moral claim based on relation, and it kills by neglect. In the Church’s life this breakdown of presumed relationality prior to willing it is reflected in the privatization of charity, its reduction from a robust gift of social cohesion to an individually willed act of selflessness. There is not much urgency to it, certainly not like in the parable of the Good Samaritan. There is only me, wanting to help.

The eclipse of human relationality as a fundamental given of politics and law is the legacy of a post-Kantian search for an expression of law that serves as a kind of imperative derived a priori and applied universally. The tragedy of our age is that the a priori universal that seems to govern our moral/political discourse is that of individual autonomy and the radical freedom of the will. Limitation of freedom by secondary laws is permitted only in so far as the freedom is perceived to cause injury to another. At present the “perception of injury” that society permits to be legally prohibited capriciously excludes vast swaths of the population from the unborn to the comatose patent, with the poor and the immigrant standing temporally somewhere in between.

In our current social predicament law is conceived as primarily a matter of discerning how to avoid the evils that unrestrained relationality might cause to the good of national sovereignty, community safety and personal rights. This state of affairs is precisely the result of the dropping out of our political consciousness a sense of legally expressed positive norms that govern the prior good of human relationality. Law as aimed at promoting the good ordering of relations, so that goods can be achieved by individuals and families within a community, seems to have passed out of our perception of social order.

We seem also to have lost the public and habitual ability to derive principles and then discern their applicability within contingent historical circumstances. Politics, and by extension, law, is increasingly perceived as ahistorical. This is to say, the principles, or facts, once assembled, are treated as universal imperatives that admit of no adaptation to particular historical circumstances. The law is the law. If we seem to be facing a choice between extremes, between high border walls on one side and open borders on another, it is because the discourse does not have room for integrating principles. Only in a political universe where law is conceived as essentially a collection of universal norms that are prohibitive of evil—evil understood minimally as causing obvious injury to another– and not also aimed at promoting the good of human relationality, is this poverty possible.

+++

Catholic moral life and thought is essentially integrative, that is to say, it assembles relevant aspects of a human situation and in so doing begins the work of forming an evaluative judgment about how particular situations do or do not attain to the more universal human goods like life, family and work. The move to the particular application is a move of practical reason that assesses goods and circumstances in a prioritized way. This way of thinking and speaking is essentially dialogical and integrative. It flows from a tradition of moral discourse that finds exemplary, though not exclusive, expression in Saint Thomas. The move from the reality of historical humanity, to the consideration of prioritized universal human goods, and then a renewed consideration of how to support these goods among particular peoples and historical circumstances is the social analogue to the Thomistic return to the phantasm. (7) Such dialogical movement is a necessary and always needed verification of rational adequatio ad rem socialem. The move from the particular to the universal back to the particular again is basic in Catholic social teaching.

People do this kind of reasoning all the time; you do not need a degree in philosophy or theology to have a habitual sense of this. Health is a human good, so we try to eat healthy foods and get some exercise and enough sleep. But if our child is sick and we have to drop everything to take her to the hospital, and stay up at night with her, and eat peanut butter and jelly because there is nothing else available, at least until she gets better, then we are spontaneously re-ordering our principled priorities. This kind of thinking is not outside of our experience, but together with charity it has been privatized. There is little concourse between the moral reasoning of individuals and the moral discourse of the political order.

+++

The papacy in contemporary times, from Pope Pius XII to Pope Francis, has spoken with increasing urgency about the phenomenon of human migration, and what a Christian and politically responsible response looks like. The development of the Magisterium on this issue has been largely a matter of expressing how a theological anthropology rooted in the Scriptural tradition lived in the Church and interpretive of the natural law impacts the social order as it develops and changes. This responds to a recognition that the primordial goods of human life, family and social cohesion have been radically affected by the development of the modern nation-state and the emergence of post-modern global economic structures. The papal magisterium thus expresses principles, and then asks that the principles be applied in a practical way to the particular, and often shifting conditions on the ground.

How immigration policy is formulated in the United States is an example of the move to particular application of principles. How a particular border patrol agent applies the policy when interviewing a 14 year old apprehended at the Rio Grande River is the move to the most particular. It is at these more particular levels, though, that the Church is often told she has no relevance to the conversation. Often our own people do not know what to make of what bishops say about the application of principles to the issue of immigration.

It is important that we understand, however, that if the Church as teacher, and if Catholics in general, cannot engage actively in the articulation of norms that require careful prudential application in law and in practice, then we are, de facto, limiting ourselves to the poverty of the post-Kantian search for ahistorical universal norms I spoke about earlier. The Church does teach norms that admit of no exceptions, but the culture suffers and persons suffer if we do not also temember that we also teach about human goods that must be balanced practically and politically in a prioritized way.

It is to this aspect of Catholic life and the just treatment of immigrants that I now wish to turn. To do this, I will use a document issued jointly by the United States Bishops Conference and the Mexican Bishops Conference in 2003. The discussion of principles found there is found in similar form in other documents, but this one remains particularly relevant and lends itself to the kind of discourse I am describing.

+++

Unamuno on the King of landless exiles:

«I have no man», we say in the anguish

of mortal life; yet you [Christ] respond:

Such is the Man, King of the nations

of the landless exiles, of the Holy Church,

of the people without a home that goes crossing

the mortal desert behind the banner

and cypher of the eternal, which is the cross! (8)

Love of country and the pursuit of justice within a sovereign nation need not be seen as exclusive of charity and justice for a suffering immigrant population that is either already here, or is seeking entry. Thus, for example, the first principle enunciated some years ago in the joint letter from the US and Mexican bishops Conferences indicates that persons have a fundamental right to find opportunities in their homeland. (9)

This flows from a basic human reality: we have in us a natural love for our own homelands and the cultures that flourish there. This is true in the United States and it is true in Mexico or in Honduras. As a basic norm, people and families should be able to live, raise their families, work and enjoy basic human goods like security, and education in their native land. Most people would prefer to stay in the country where they were born, if conditions permit it. Many immigrant parents I know dream of one day being able to go back home and raise their children there, if conditions back home would allow.

There are many places in the world where there is a state of affairs that roughly provides the kind of social equilibrium that this principle describes; and there are many places where these conditions are nearly non-existent. Immigration tends to happen when people do not judge they have a chance to survive and raise a family in their native place.

This principle (i.e. people have a right to stay home) has the character of a kind of temporal end, and as such is rightly held in sight as we discuss the other principles that the bishops identify as morally relevant to the just treatment of immigrants. It is also a principle which is admittedly beyond your or my personal ability to enact today, by personal effort alone. We can contribute to it (look for the Catholic Relief Services website), but it is not something we can do in the same way we can make a sandwich for a person who is hungry.

The principle points to the need to formulate a cooperative and cohesive response from peoples and nations around the world, principally in developmental support for countries where poverty and insecurity exist in devastating proportions. Such efforts take time to have effect, and certainly the bishops do not suggest that we alone in the United States are solely responsible for helping promote the human good in other parts of the world.

Thus, there is a second, closely related consideration that flows from the first: Persons have the right to migrate to support themselves and their families. The Church recognizes that all the goods of the earth belong to all people. When persons cannot find employment in their country of origin to support themselves and their families, they have a right to find work elsewhere in order to survive. Sovereign nations should provide ways to accommodate this right. (10)

Thus, realistically, immigration is most often the human response to a moment of crisis, of people responding to hardship and fear. Today, immigrants are often pawns in a harsh power-game that involves governments on one side and criminality and corruption on the other. In some parts of the world the distinction between the two is not so easy to see.

Two things that I want to note about this principle, which is in some ways the nub of the question today. The principle exists in relation to the Catholic teaching about the universal destination of all goods. Like the right to private property, sovereign control of borders is not an absolute; it is rightly accommodated in view of the right of persons to survive. (11) Further, there is a recognition that this principle of social good must be politically accommodated as an expression of political responsibility. This implies a willingness to revisit how well a nation is responding to conditions of poverty, drought and famine within its own borders and in other countries. In times of crisis, a global or hemispheric response is called for, and this may require a more generous policy of receptivity to immigrants. In principle, though, a Catholic cannot say “that is none of our nation’s concern”.

Subordinated to these two general principles is another that can only be understood in relation to the prior more universal principles. Sovereign nations do have the right to control their borders. (12) This principle predates the modern nation-state, though it accommodates to the current reality. (13) This principle is rooted in a judgment about the good of promoting a cohesive social order that acknowledges the diversity of familial, cultural, social and national identity patterns. The neighbor is the neighbor precisely because we live distinct familial and national dynamics. Law recognizes this, and history shows it is a principle that has stable meaning and yet admits of shifting applications over time.

In the current context, the right to enforce internationally recognized borders is itself conditioned by a responsibility to do so with an eye on the previous principles articulated, and on the realistic appraisal of national resources. More powerful economic nations, which have the ability to protect and feed their residents, have a stronger obligation to accommodate migration flows. (14) This is a call to application on the level of political prudence of the Scriptural injunction Share your bread with the hungry; shelter the oppressed and the homeless. Clothe the naked when you see them, and turn not your back on your own (Is 58, 7).

The final two principles articulated in the joint document move decidedly to the particular, and thus begin to address the practical question of how to respond to persons who are at the border, or who wish to come into the United States because of what amounts to the proximate danger of perishing in their homeland. Thus, the United States and Mexican bishops integrate into the narrative of principles a special word about refugees and asylum seekers: They should be afforded protection. Those who flee wars and persecution should be protected by the global community. This requires, at a minimum, that migrants have a right to claim refugee status without incarceration and to have their claims fully considered by a competent authority. (15)

And at its most immediate, the bishops reiterate the obligation of those charged with law enforcement to do so with due regard to the dignity of persons who migrate: Regardless of their legal status, migrants, like all persons, possess inherent human dignity that should be respected. Often they are subject to punitive laws and harsh treatment from enforcement officers from both receiving and transit countries. Government policies that respect the basic human rights of the undocumented are necessary. (16) Here, the point is about how persons entering the country without the documentary permissions a sovereign state may require are in fact treated when apprehended. As “Strangers no Longer” puts it: While the sovereign state may impose reasonable limits on immigration, the common good is not served when the basic human rights of the individual are violated. (17)

The call of the American Catholic bishops for a comprehensive reform of the current immigration law is mostly about how to balance the goods outlined in these principles I have outlined. It is a call for reasonable political will, and it involves a realistic accommodation of the particular situations affecting immigrants today. It is not adequate, from a Catholic point of view, to base a national immigration policy on purely economic criteria. The fact of global economic displacements, of war or lawless violence in numerous parts of the world must be addressed in a way that reflects a realistic response to a proximate threat to human life and its proximate goods.

In particular, national policy should reflect the fact that the family is the most basic pedagogical vehicle for wider human and social cohesion. For this reason, the bishops continue to ask that the law recognize that deportations resulting in the separation of parents and children is harmful to the good individuals, of the family, and of the country. If families are separated, the whole fabric of the culture unravels. The breakdown of the family structure vitiates the social good because it directly affects the formation of the young.

In the political order, to frame the discussion around cases of obvious crimes and misdeeds committed by members of “the immigrant population”, for example, often aims rhetorically to short-circuit the discussion. Within a generous response to immigrant persons and families can be accommodated a legitimate concern for stopping criminal elements from injuring others, either here or abroad. A great many immigrants that I know are seeking permission to stay in the United States because they are fleeing the very same kinds of criminal elements and activities that we rightly do not want causing harm here. One of the tragedies of the mutually exclusive narratives, and of our anemic discourse is that we do not currently have a an effective legal way to distinguish between immigrants who are fleeing criminals, and immigrants who are criminals.

+++

Let us return now to the concrete particular, the phantasm of our social thinking, the reckoning rod and builder’s square of our human living.

A couple of years ago I met a young man in Honduras, 16 years old. His parents were either dead or gone, he didn’t say. He had recently been summarily deported from Mexico. He told me he had tried 5 times to get the United States, because there was nothing for him at home; the gangs would kill him if he stayed. He said he would try again. He wanted to have a life, he said, a job, maybe a little house and get married. And if he didn’t make it to the US, he would try to live in Mexico. At least there, he said, you can have a life. I think of this young man often.

I do not tell you about him to stir your sentiments. I tell you because there are hundreds of thousands like him, who live at the edge of human society, They are the ones who are told there is no room for you here, and there is no room for you anywhere else: «it is not our concern what happens to you».

He is just one young man. But our political activity as Catholics must keep faith with him if we are to keep faith with Christ. Maybe he is still alive, maybe he is in Mexico; maybe he has a grandmother somewhere praying for him. And maybe someone will respond to him. He is in some real way Christ Himself whom Velázquez and Unamuno sought, that particular wounded flesh, to whom also we we must ultimately return.

While the earth in loneliness sleeps,

there watches the white moon; the Man watches

from his Cross, while men sleep;

watches now the man without blood, the Man white

like the moon of the black night;

watches now the Man that gave all his blood

that the peoples might know that they are men. (18)

+++

Notes:

1) Miguel de Unamuno, “El Cristo de Velázquez”, I, iv:

Mientras la tierra sueña solitaria,

vela la blanca luna; vela el Hombre

desde su cruz, mientras los hombres sueñan;

vela el Hombre sin sangre, el Hombre blanco

como la luna de la noche negra;

vela el Hombre que dio toda su sangre

por que las gentes sepan que son hombres.

2) Thomas Pfau: Minding the Modern, (University of Notre Dame Press, 2013).

3) See Saint Bonaventure, Life of Francis.

4) Miguel de Unamuno, “El Cristo de Velázquez”, I, vi:

Tú eres el Hombre, la Razón, la Norma,

tu cruz es nuestra vara, la medida

del dolor que sublima, y es la escuadra

de nuestra derechura: ella endereza

cuando caído al corazón del hombre.

Tú has humanado al universo, Cristo.

“¡He aquí el Hombre!” por quien Dios es algo.

5) Caritas in Veritate, no. 7.

6) The empiricism and positivism that are the godparents of this emphasis on purely willed relations have roots in the earlier adoption of univocal discourse over the analogical, and the voluntarisms that followed upon it. See John Milbank (Beyond Secular Order: Wiley and Sons, 2013), and Charles Taylor (A Secular Age: Belknap Press, Harvard, 2007)

7) Summa Theologiae, Ia, 84, 7.

8) Miguel de Unamuno, “El Cristo de Velázquez”, I, vi:

«¡No tengo Hombre!”, decimos en los trances

de vida mortal; mas Tú contestas:

¡Tal es el Hombre, Rey de las naciones

de desterrados, de la Iglesia Santa,

del pueblo sin hogar que va cruzando

el desierto mortal tras de la enseña

y cifra de lo eterno, que es la cruz!…

9) Strangers No Longer: Together on the Journey of Hope, Issued by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Conferencia del Episcopado Mexicano, January 22, 2003, no 34: All persons have the right to find in their own countries the economic, political, and social opportunities to live in dignity and achieve a full life through the use of their God-given gifts. In this context, work that provides a just, living wage is a basic human need.

10) Strangers No Longer, no. 35.

11) CCC no. 2404: «In his use of things man should regard the external goods he legitimately owns not merely as exclusive to himself but common to others also, in the sense that they can benefit others as well as himself.» The ownership of any property makes its holder a steward of Providence, with the task of making it fruitful and communicating its benefits to others, first of all his family.

12) Strangers no Longer, no 36: The Church recognizes the right of sovereign nations to control their territories but rejects such control when it is exerted merely for the purpose of acquiring additional wealth. More powerful economic nations, which have the ability to protect and feed their residents, have a stronger obligation to accommodate migration flows.

13) See Jacques Maritain, Man and the State.

14) Strangers no Longer, no. 36.

15) Strangers no Longer, no. 37.

16) Strangers no Longer, no. 38.

17) Strangers no Longer, no. 39.

18) Miguel de Unamuno, “El Cristo de Velázquez” I, iv:

Mientras la tierra sueña solitaria,

vela la blanca luna; vela el Hombre

desde su cruz, mientras los hombres sueñan;

vela el Hombre sin sangre, el Hombre blanco

como la luna de la noche negra;

vela el Hombre que dio toda su sangre

por que las gentes sepan que son hombres.

—

+df