Dignitatis Humanae, the Convergence of Traditions, and the Freedom of the Church: I gave this lecture as part of a larger conference at the University of Notre Dame Law School, commemorating the 50th Anniversary of Dignitatis Humanae. As I re-read it recently, I thought of some things I might now want to say differently, and certainly, I would want to have then said more humbly. +df

Notre Dame University

5 November 2015

It is right and just that the Church recollect gratefully the the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of the Second Vatican Council’s Decree on Religious Freedom, Dignitatis Humanae. And I am honored to participate in an event here at Notre Dame University contributing to the Church’s worthy aim.

I would like to speak about Dignitatis Humanae this evening using the image of a tryptic. I will invite you to look at the left side, so to speak, first. On it I will depict something of the intellectual issues at play when the document was being forged. Secondly I will invite you to look at the right side, where I will sketch some relevant points about cultural history in the West, insofar as they touch on the issues of human individuality and freedom. Finally, I will have us look at the center panel, which will hopefully say something worthwhile about where the teaching of DH points us today.

I. The coalescing of doctrine:

First, a look at the left panel. Within the tradition of the Church, DH represents a magisterial judgment about religious freedom. Just as importantly, it represents a magisterial judgement about the proper way to frame the issue. This should not be surprising; this is what Council’s do. It is comparable to Trent’s decision to frame the question of good works within the Decree on Justification. (1)

If one looks at the redaction history of DH, comparing the earliest drafts to the fifth and final, taking particular note of the changes made from the third draft to the last, it appears clear that the mind of the bishops coalesced around framing the issue within the theological tradition articulating the freedom required for the act of faith. (2) It could have been framed otherwise, for many options lay open to them. The document states in number 10:

«It is the chief tenet of Catholic teaching, contained in the word of God and constantly proclaimed by the Fathers, that man’s response to God in faith should be voluntary; no one is to be forced, therefore, to embrace the faith against his will. The act of faith is of its very nature a voluntary act. For man, redeemed by Christ the Savior and called to be an adopted son through Jesus Christ, cannot hold fast to God as he reveals himself unless, drawn by the Father, he offers to God a rational and free submission of faith.» (3)

The Conciliar judgment about the frame and context of the teaching suggests that related topics such as the dignity of the human person, human freedom, and human intellectuality are best understood from the point of view of the revelation. Simply put, the human person as a rational and choosing being is best perceived from the vantage of the highest acts open to us in this life, namely the human dynamic of truth apprehended and freely chosen in faith. That this human dynamic happens with the aid of grace does not obscure its essentially human character. On the contrary, it renders it more intelligible.

There is an analogy here between Chalcedon on the divine person and its relation to later philosophical development of the human being as person, and the teaching of DH on the freedom of the act of faith and its relation to a political philosophy of religious freedom. Only, as is obvious, the theological clarification of Chalcedon about persona predated the subsequent philosophical development, while the theological clarity about the act of faith in some way looks back at a prior philosophical discourse about political philosophy. I simply note the fact at this point. Though, it is also true that the history of political discourse about religious freedom, inasmuch as it flows a winding and sometimes violent path of thought about the human person, (the French Revolution and the Spanish Civil War are part of this path) itself depends in some ways on the grand impetus flowing out of Chalcedon.

As I mentioned, the Council Fathers had other options open to them. John Courtney Murray argued for a framing that focused on the juridical limits of the civil authority, proposing thereby that the teaching of the document focus primarily upon the Church’s recognition of “an objective truth manifested to the people of our time by their own consciousness”. (4) He bristles somewhat at the prospect of understanding religious freedom as a “theological concept which has juridical consequences». (5) He favored the position that religious freedom is formally a juridical and constitutional concept, which is “validated in the concrete by a convergence of theological, ethical, political and jurisprudential argument”. (6)

Now, Murray was a powerful defender of the Natural Law as the best achievement of the perennial philosophy of the West for sustaining a just social order. Nothing in my preparations for this lecture was more delightful than reading Murray’s essay The Doctrine Lives: the Eternal Return of Natural Law. (7) The intellectual air he breathed seems to have been the clean and crisp mountain air of the Thomistic revival of ethical and political thought, sustained by a rediscovery of the pre-modern sense of Thomistic social doctrine. This air owes a great deal to Leo XIII and Pius XII.

Now then, in the book entitled Freedom, Truth, and Human Dignity David Schindler writes an important essay unfolding the relationship of the final document to the theological influences of its time. (8) He examines in particular how Father John Courtney Murray understood the teaching of DH, and suggests that he underestimates the importance of the theological recasting that occurred between the third and final drafts.

Schindler argues that the approved text decisively tilts the document away from a primarily juridical context to a context properly situated in patristic and medieval theological anthropology. Schindler is not the first to note this. Cardinal Dulles, not too long before his death, gently chided Murray’s characterization of the teaching as the Church “coming late, with the great guns of her authority, to a war that had already been won.” (9) Dulles here is picking up on Murray’s general sense that DH is a conciliar acceptance and clarification of basically a modern social and political consensus. Here is an example of the way Murray characterized the teaching of DH, the kind of text that I think prompted Dulles’ comment:

«First we must note that the doctrine of the Declaration is today supported by the sense and near unanimous consent of the human race. This is also intimated at the very beginning of the Declaration. The Declaration also suggests that this consent does not rely upon the laicist ideology so widespread in the nineteenth century but upon the increasingly worldwide consciousness of the dignity of the human person. It relies, therefore, upon an objective truth manifested to the people of our time by their own consciousness. Before adducing other arguments, then, the presupposition obtains and prevails that the teaching of the Declaration is true. Securus enim iudicat orbis terrarum.» (10)

It is hard to read this without hearing Murray center our attention of what is affirmed in DH, on its source in a conciliar approbation and clarification of near world-wide consensus. The arguments in favor of the doctrine clarify and purify the consensus of its 19th Century baggage, but they do not form the basis of the Conciliar teaching on religious freedom. “It relies,” Murray says, “on an objective truth manifested to the people of our time by their own consciousness.” (11)

Both Schindler and Dulles agree that the interventions of the then Archbishop of Cracow, Poland, Carol Wojtyla and others, reframed the teaching in ways Murray was reluctant to admit. Dulles’ article is well worth re-reading, as it admirably traces the properly theological anthropology Wojtyla argued for in the document, and his subsequent expansion of that teaching throughout his pontificate. Schindler, on the other hand, is interested in unearthing the problematics implicit in Murray’s perspective.

To be brief about it, Schindler argues that in his post-conciliar commentaries, Murray downplayed the importance of the relationship between freedom and truth articulated in the final text. Thus, Murray’s reading obscures Saint Thomas’s conception of freedom as freedom for the sake of the truth and the pursuit of human excellence. On Schindler’s reading of Murray, he implicitly grants as normative the secular state’s grounding in the freedom of indifference. In other words, Murray seeking to defend religious freedom as a Thomist, actually gives the secular state to Ockham. This is my characterization of Schindler’s position, not Schindler’s.

Let us look at Murray for a moment, though. He emphasized that the core of the teaching in DH was negative in nature, laying out what the state may not do in relation to persons and communities of religious faith. Murray himself puts it this way:

“[T]he concept of religious freedom includes a two-fold immunity from coercion. First in the sphere of religion, no one is to be compelled to act against his conscience. […] Second, in the sphere of religion no one is to be impeded from acting according to his conscience—in public or in private, alone or in association with others.” (12)

This immunity from coercion is rooted in a conciliar teaching about the juridical order, a solemn statement affirming that the public order is incompetent in matters of religious faith, and since these matters touch on the most sensitive aspects of human life and conscience, can in no way act coercively. To do so is a violation of human dignity. This teaching is expressed to cohere with the right of the Church, and by extension, other religious bodies, to act freely within human society, in accord with the content of the body’s religious teaching. For Murray, this is a vindication of the Anglo-American liberal tradition expressed in the Declaration of Independence and in the United States Constitution over the Continental European historical construct that gave us the French Revolution and the Spanish Civil War.

Put perhaps too simply, Murray favors the first paragraph of DH as the principal lens for its interpretation. There, where it says, for example:

«Men and women of our time are becoming more conscious every day of the dignity of the human person. Increasing numbers demand that in acting they enjoy and make use of their own counsel and a responsible freedom, not impelled by coercion but moved by a sense of duty. They also demand that juridical limits be set to the public power, in order that the rightful freedom of persons and associations not be excessively restricted.» (13)

Schindler, and Dulles I think, prefer number 2 of DH as the defining lens:

«In addition, this Council declares that the right to religious freedom has its foundation in the very dignity of the human person, as known from both the revealed word of God and reason itself. This right of the human person to religious freedom must be acknowledged in the juridical order of society, so that it becomes a civil right.» (14)

DH 2, with its emphasis on human dignity as rooted in our being “endowed with reason and free will and therefore privileged with personal responsibility” states the matter in terms of a positive good of the human person with juridical consequences. This is a properly theological perspective, citing the revealed Word of God as the first fount. (15) The statement is situated, I think, in that space where revelation reveals what human reason can otherwise know without revelation, but only «with great difficulty». (16) Further, this theological root is elaborated in DH 9 where the teaching on religious freedom is discussed in the light of revelation.

If one compares the third draft of DH, the draft wherein Murray had his strongest influence, to the final text, key repositioning of the teaching occurs. For example, important references at the beginning and throughout on the Church’s drawing from sacred tradition and her own tradition in order to put forth this teaching emerge forcefully. (17)

Thus, I would suggest the drafting of the text represented a dance between at least two different kinds of Thomism: Murray’s Thomism of political philosophy, and the theological Thomism of Wojtyla and others. Ultimately, the Council Fathers relativized the lucid and resilient tradition of Thomistic political philosophical thought. By relativized, I mean, made it to be seen in relation to the higher theological light.

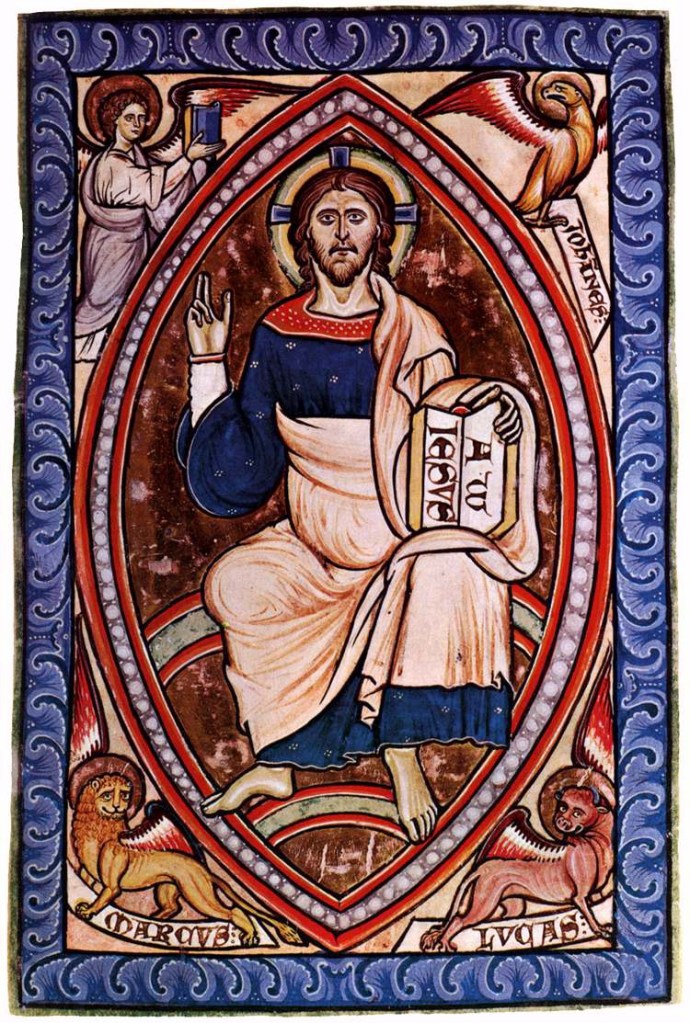

The theological Thomists, who owed much to figures like de Lubac and Gilson, read the Secunda Pars, especially the prologue, in the light of the Trinitarian theology of the Prima Pars. Trinitarian doctrine passes into moral theology by way of the patristic and medieval doctrine of man as the imago Dei. (18) Thus, what DH proposes is teaching rooted in revelation, clear and mystery-laden at the same time. Clear because the prerogatives and operations of reason and will are discernible to all; mystery-laden because the light of the Trinity and its reflections in the human soul are only partially known in this life. Well, that is the way of theology.

Wojtyla’s theological Thomism, which takes revelation as properly informing what can become a formally philosophical discussion, provided the decisive tilt to the doctrine of DH, contextualizing Murray’s more philosophical Thomism within itself. (19) To be fair, Murray, after the Council, seems not to have seen it that way. He is somewhat befuddled by the section on religious freedom in the light of revelation, and seems not to have given it his full attention. (20)

Thus, to conclude this first panel of the tryptic, then, I wish to propose that to hold that the teaching of DH is primarily theological does not necessarily suggest, as Murray feared, that the doctrine is altogether out of reach of non-theological discourses such as political philosophy or constitutional theory. (21) It does mean though, that when we engage in the current discussions about religious freedom within a contemporary society of religious pluralism and governmental indifference to religious doctrines, we have to be both reasonable and aware of how our political philosophy receives direction from properly theological anthropology.

II. The cultural trek toward Individual Autonomy:

I would like to shift panels at this point, to one that looks at the historical cultural context of some of the key elements in the teaching of DH. In 1949, Maritain in his seminal book Man and the State asked us to pursue “a sound philosophy of modern history.” (22) He was pointing to the fact that discussions about the relation of the Church to civil society must be for us more consciously informed by the ways the Christian revelation has in fact influenced the course of Western thought about this issue. Not to do so makes us prisoners of 18th and 19th Century re-writings of history.

In his book Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism, Larry Siedentop offers an engaging study of the development of Christian life and thought and its impact on ancient society, and beyond. (23) In many ways, without my claiming that he is responding to Maritain, he is in fact offering a kind of response to the general challenge.

I would like to focus on two of his central contentions. First, that Christianity’s appearance in the ancient world hastened and gave decisive feature to the cultural demise of the Household as the principal vehicle for religious expression and thus social identity. Secondly, Christianity in the Gospels, in Saint Paul, and as transmitted to the Middle Ages through the figure of Saint Augustine, set in motion the decisive development of a metaphysics of the will.

Let us look briefly at the first issue. Before Athens and Sparta, in the world Homer would have found recognizable, ancient familial culture was sacral to the point of saturation. This set in place a social order of natural inequality. This social order is reflected in later Greek philosophies of nature, where the rationality of the cosmos is delimited by metaphysical inequalities.

Social identity was defined by roles assigned by relation to the governance and survival of the familial hearth. There was no individual identity apart from this relation. This was particularly striking in the case of younger daughters and sons, who were consigned to ancillary roles in support of the survival aims of the paterfamilias who acted as high priest of the family. Indeed, the early cities did not have an identity other than the tolerant association of sacral households who depended on the familial gods and sacrifices to sustain social life.

Christianity, with particular emphasis on Pauline preaching, offered a lived anthropology that overcame in many ways the sacral stratification that enforced a natural inequality. The Christian insistence on the individual encounter with the grace of Christ implied the ascendency of individuals as fundamentally equal before God. Conversion is possible for an individual, and it trumps pre-existing social identities rooted in the sacral household. We need only think of Saint Lucy or Saint Agatha as representing radical rejection of a received identity to grasp the point here.

Seidentop, for example, traces the social influence of the doctrine of equality before God and of grace operating in the individual’s autonomous will through the varied monastic movements. He also discusses the gradual repositioning of the natural philosophy of the ancients. There was a powerful move afoot away from the natural hierarchy of the ancients, which when not hostile to it, devalued matter in comparison with spirit and form. The intellectual move toward the consideration of the dignity of the individual (who after all is individual precisely as enfleshed) opened up, we could say, the cold necessities of ancient metaphysics. Put simply, the incarnation of the WORD, over time, turned the ancient metaphysical cosmology on its head.

As a result, the free human agent finds a place within the cosmos to act freely. This dynamic resisted the frequent cultural resurgence of identity based on natural inequalities reminiscent of the ancient world. Feudalism is a reminiscent form of cultural inequality. It grew, but did not ultimately prevail in the West. Ironically, the centralization of civil authority in a monarch was early on seen as a remedy to feudal inequalities. All were equal before the King, just as all were equal before God. Thus, the original Christian recognition of the individual as equal before God resisted uncontested historical resurgences of stratification and forms of natural hierarchy. Medieval moves toward the recognition of corporate rights of associations of individuals, and toward the recognition of individual rights before the claims of the wider community continued to weave their way toward modernity.

Closely allied to this reconceptualization of the cosmos away from the dominance of natural inequality is the emergence of the will as the agent of human individual encounter with grace. Augustine, of course, largely as the Western conduit for Pauline teaching, brings this to lucid articulation. Siedentop observes, rightly I think, that the ancients did not have a concept of will that is comparable to the post-Christian development. The dynamic unleased by intellectual consideration of the power of human willing, will with time show itself in remarkable, sometimes, contradictory cultural ways.

Through the patristic era and through the high Middle Ages these two notions– the natural equality of persons before God, and the emergence of the human will as an object of explicit philosophical and theological reflection– developed within the context of a communal self-understanding. This kept in tension the given reality of a pre-existing community culture with the autonomy of the person before God. Saint Francis’ decision to leave his father’s world of commerce is a medieval example of this tension, and one possible outcome.

Whereas in the ancient world these tensions expressed themselves in favor of young family members choosing against their parents wishes, or against the law of the Empire, to become Christian, in the later medieval context the tension expresses itself in a resistance to an ecclesial enforcement of Church discipline and moral norms.

Thus, the cultural trek that gets us to where we are today is born from post-Reformation efforts to begin recasting of the issue of freedom in relation to the Church. But the dual notions of equality of souls before God, and the prerogatives of the human will, already traditionally Christian notions, are on full display in this recasting. They set the late medieval and renaissance stage for the move in early modernity to the forging of the secular state, either hostile or indifferent to the Church.

Seidentop argues against the notion that the modern development of the secular state is rooted primarily in a Renaissance rediscovery of ancient individualism and democracy, free from sacral presuppositions. Actually he thinks this to be a severely flawed view of what has happened. But it is the view that has dominated the social and philosophical debate about the Church’s place in society, and about religious freedom. He further makes the case that this faulty narrative severely debilitates the West in its current political engagement with non-Western cultures and societies.

An important upshot of a more accurate historical narrative highlights the fact that our current struggles over the issue of religious freedom are less like struggles between sworn enemies, and more like struggles between a mother and her adult daughter. Even if historians since the Renaissance have highlighted a parentage stemming from ancient Greece and Rome, and distanced themselves from the Church as the crazy aunt who took possession of the house for a while, the truth is otherwise. Greece and Rome may be modernity’s grandparents, but the Church is modernity’s mother, and in a sense we are engaged in a struggle that already implies a relation perhaps neither the Church or the modern state is happy to admit is a given.

But it is a given, and I think it is fair to say that Murray had a fine sense of this relation. Murray himself agrees with Seidentop about the dangers of faulty historical narratives, although he comes at the matter from a different direction. He is at pains to dissociate the American constitution from Enlightenment thought, especially in the forms that created the violent bifurcations of the French Revolution. Speaking of the Bill of Rights, Murray says:

“The “man” whose rights are guaranteed in the face of law and government is, whether he knows it or not, the Christian man,who had learned to know his own personal dignity in the school of Christian faith.” (24)

Finally, for this panel of the tryptic, I would suggest that from a historical point of view, an accurate narrative recognizes the decisive fact that the issues of equality and freedom became disengaged at some point from the theological context that gave them birth. This was true first inside the Church and then outside the Church. Perhaps, in some non-Hegelian sense, this was inevitable, given the historical contingencies that flowed from feudalism and the late rise of absolute monarchy as a sort of remedy for feudalisms social inequalities.

But still, it is important to note that DH repositions, for the Church, the discussion about Church, society and freedom, within a properly theological frame. It remains to be seen if it is possible for us to influence the wider social fabric by means of such a recovery of our best lights. But DH would insist that we are better off looking at the issue from the perspective of our best lights: The Gospel narratives, Paul, Augustine, and Thomas (understood as the heir of Augustine more than as the heir of Aristotle). This, I think, is the perspective DH proposes as best suited for the Church’s global engagement on issues of religious freedom.

I take from this a sense that within the Church, we need to reestablish the vigorous links between theology, philosophy and jurisprudence, recognizing that philosophy and law do not lose their autonomy when informed and guided by the revelation.

III. The Church’s Responsibility towards Civil Society:

Now then in the final panel of the tryptic, the one at the center, I would like to look first at the implications of what I have sketched so far. First, a brief nod of respect to Jacques Maritain, who was keenly aware of the light political philosophy and legal theory can derive from the higher sciences. How one conceives the relation between the political philosophy of DH and the sources in revelation that give it proper context and finality was of great concern to him. He had a different way of speaking of these things, than either Murray or Schindler, but it does not constitute a foreign language.

For example, Maritain spoke of certain “immutable principles that must be applied” in the future if we are to forge a realistic path forward on the issues of the relation of the Church to civil, secular society. (25) Among these principles he listed such things as “The freedom of the Church [as] both a God-given right belonging to her and as a requirement of the common good of political society”. Another principle: “the Church and State must cooperate”.

The period of Roman persecution, and the world of the high Middle Ages represent different analogous working out of these immutable principles in the concrete world of historical contingencies. Historical contingencies may be contingent, but they have the power to set a trajectory within which human freedom may or may not wisely operate. Much has happened to Western society since the Renaissance and Reformation. Maritain certainly thought that our task is to apply these principles within our current context. These applications will bear analogous relation to past expressions. Writing two decades before DH he could describe the Church’s future role in society this way:

“The superiority of the Church is the moral power with which she vitally influences, penetrates, and quickens, as a spiritual leaven, temporal existence and the inner energies of nature, so as to carry them to a higher and more perfect in their own order,…” (26)

In a way, though, he is anticipating a future for the Church that is more like late antiquity than like the 19th Century. It is the analogous application of these principles that for Maritain speaking in 1949, could only salute from afar. Perhaps he was overly optimistic; or more likely, it is too early for us to tell.

Nevertheless, I think his focus upon a Church that is free to exert her influence, primarily through the grace of the preaching of the Gospel and the life of the sacraments is one deeply in tune with the thrust of DH. Perhaps the words of Blessed Pope Paul VI, who, as you know had a deep appreciation for Maritain, are helpful here. Speaking to political leaders at the conclusion of the Council, he wrote the following:

«What does the Church ask of you today? She tells you in one of the major documents of this council. She asks of you only liberty, the liberty to believe and to preach her faith, the freedom to love God and serve Him, the freedom to live and to bring to men her message of life. Do not fear her […] Allow Christ to exercise his purifying action on society.» (27)

Theologically speaking, from inside the Church, our responsibility to defend religious freedom is a given of the revelation. The Church must be free to do as the Lord told her to do, namely devote her life to leading the human race to eternal life. This communal leading is itself the purifying action that Pope Paul VI spoke about, and it is the spiritual leaven that quickens human society that Maritain spoke about.

But again, neither the secular state nor the modern non-Christian theocratic state can be expected to take this mission at face value. Hence, it is necessary to look a little further.

It is interesting to note that the opening sections of DH deal primarily with the freedom of individuals from coercive intrusions by the government in matters religious. This is, I think a recognition in 1965 (perhaps Murray’s «consensus») that modernity begins with individuals not with the communal. Individuals are rational and free, and because of this institutions can be said to be so. This is a point in philosophical anthropology. Subsequently, in number 4, the document begins to speak of religious bodies and communities enjoying the same freedom. Here again, this is presented in terms that we could call an evident principle of philosophical anthropology, namely that we are social creatures by definition. Some philosophical schools, namely those stemming from Locke would wrinkle a brow at this, but other schools might not. Aristotle certainly would have had no problem with it.

In any case, organized bodies comprised of freely associated believers must be allowed to exercise their religious doctrine in society without coercion. The Council admits that their may be limits, but only insofar as they insure just order.

It is in number 13, however, that the document shifts to speak formally of the Catholic Church’s freedom to operate in society. This would be the place, so to speak, from which Paul VI utters his plea to rulers for the Church’s freedom. Number 13 offers a statement flowing from the nature of the Church as founded by Christ.

The Council describes it as a “sacred freedom with which the Only Begotten Son of God endowed the Church”. (28) Obviously this is a theological principal, and hence one that we may suspect is not in itself persuasive to a civil or contemporary theocratic authority. It is akin to a line used by Maritain much earlier when he said:

“The Freedom of the Church does express the very independence of the Incarnate Word.” (29)

It requires not too much theology to recognize the truth of this from the point of view of the Church. Nor does it require too much imagination to recognize how the freedom of the Word Incarnate was a freedom violently constrained by the civil power. And that is the nub of the problem. Of course, as He said: “No one takes my life from me, I give it freely.” (30) That must be a line the Church meditates frequently if she truly considers herself the expression of the freedom of the Incarnate WORD. There is a deep mystery there, but I will simply leave it to you to contemplate further.

What I do wish to emphasize though, is how DH number 13 also insinuates some of the reasoning in number 4 in order to make an important claim that one would hope is intelligible to a civil authority.

«Preeminent among those things that concern the good of the Church, and indeed the good of civil society itself on earth, which must always and everywhere be preserved and defended against all harm, is for the Church to enjoy as much freedom in acting as the care of man’s salvation may demand.» (31)

Here, the claim is also made that this good of the Church, namely her freedom to act without constraints to pursue the salvation of man is also “indeed a good of civil society itself on earth”. The language is found in similar form in Maritain and in Murray, and in other vigorous Thomists of the last century.

I think it is good to mark this place as the point of vital concern theologically, philosophically and in jurisprudence right now. It is a claim that straddles the line between what is accessible by revelation alone, and what is revealed, yet also accessible to reason. (32) Here is where I think we need to put our best intellectual lights to work in order to fill out the sense of this claim.

To do so makes us true to our own theological tradition, and is a necessary service to the civil society. We should be asking: “On what basis is it possible for the Church to elucidate intellectually, culturally and in the civil order, this «good of civil society» promoted by religious freedom?»

Let me briefly explain, again getting a little help from Maritain. In a real sense, that it is a good of society to allow freedom for the inculcation of doctrine about the non-temporal order is older than Aristotle. He made a good case for it. Read the Metaphysics alongside the Politics and the Ethics, and you readily see how the tension between the two spheres existed then, and how he tried to navigate his way through it. Socrates, though, a generation earlier, is in a sense a martyr to the claim that those concerned with matters touching on eternity should have space to act in the temporal order of the polis.

As Socrates and Aristotle testify, the tensions between those dedicated to the extra-temporal good have a long history of living in tension within the necessary life of the city. The issue of religious freedom is the heir to those earlier historical tensions. But, in a real sense, so have been artists, poets and musicians, or at least an argument could be made for the analogy. Maritain is vitally aware of this when he wrote in 1949:

“Thus even in the natural order, the common good of the body politic implies an intrinsic, though indirect ordination to something which transcends it.” (33)

What Maritain describes as the body politic’s “indirect ordination to something which transcends it” is nothing less than the expression of a truth about human beings. The human person, because endowed with intellect and will, cannot be reduced to a life that simply craves a peaceful social order where the state’s only obligation is to allow people to do what they will so long as the screaming is kept to an audible minimum.

There is a long and vital tradition in the West of making this kind of philosophical and cultural argument. The state need not judge the claims of the Church, of philosophers or of artists, only recognize that the freedom they require to flourish is based on a human recognition that there are more important things than better telephones, and more efficient means of human manipulation of the physical universe.

The intellectual horizon, as Pope Benedict never tired of saying, is severely reduced in our time. Contemplation of truth and beauty is not encouraged, and if acknowledged at all, is reduced to the private sphere. Such a state of affairs is not in the best interest of the human community, or the human person, because we are more than our powers to manipulate physical nature. Here, I think, Pope Francis is pointing in the same direction Benedict pointed in, only using a different dialect, so to speak. Reduction of man to economic usefulness is the deadly consequence of reducing man to the purely temporal sphere of the modern secular order. I think both Benedict and Francis would tell us that this is killing us.

The Church, like the philosopher, must have freedom to live her community life free from interference by the secular order precisely so that the goods of the whole person can have a chance to be operative and exercise their influence on the wider society. The good of the whole person thus includes our extra-temporal aspirations and concerns, and these include religious endeavors but others as well. (34)

For the Church to state that it is a good of civil society for her to be free to express and live her doctrine in society without coercion or hindrance, is for her to claim something that the civil order has in its better historical moments recognized, going back to the most ancient of our memories. But the history on the point is not always positive.

The secular order, equivalent to the political, temporal order has historically had difficulty with the prerogatives of the extra-temporal aspirations of saints, poets and philosophers. But DH is saying that the temporal political order should not impede the space for these extra-temporal aspirations. The Church cannot abide quietly while the eclipse of man is presided over by an impoverished temporal order. Thus, the Church understands that the divine mandate to teach includes a service to a society that has shoved aside its own best moments. Put another way, the divine mandate includes a mission to defend the prerogatives of reason, including speculative and contemplative reason. This is a service to reason and to the human person and thus to society, that the Church must, by divine mandate, render. What is needed then, is a robust philosophical discourse fully informed by the theological sources that prevent the reduction of man to product and producer.

In a great historical irony fitted for our times, the Church may be, for a while, the only major community and institution in the West left defending and cultivating the full expanse of human reason as a patrimony, and as a task to be fulfilled. This task will likely cost us, but if we are true to the revelation present in the person of the Word Incarnate, and if we do this freely, we will not fail to render this service to the human community.

Thank you for listening; I am honored by your kind attention.

+df

_______________

1 Trent, Decree Concerning Justification, Ch XVI.

2 Schindler and Healy, Freedom, Truth, and Human Dignity (Eerdmans, 2015) provide a new translation of DH, the textual redactions together with notable interventions on the document by particular bishops.

3 DH 10.1 (I use the Schindler translation throughout).

4 Murray, “The Human Right to Religious Freedom” in Religious Freedom, Catholic Struggles with Pluralism edited by J. Leon Hooper, SJ (John Knox Press, 1993), 233

5 Murray, “The Problem of Religious Freedom” in Religious Freedom, Catholic Struggles with Pluralism edited by J. Leon Hooper, SJ (John Knox Press, 1993), 139.

6 Murray, PRF, 139.

7 Murray, Ch 13 in We Hold These Truths, (Rowman, 2005), 267 ff.

8 Schindler, 39-210.

9 Dulles, quoting Murray, in his article entitled “John Paul II on Religious Freedom” 26-41, In “Humanitas” Christian Anthropological and Cultural Review No. 1 of the English Edition, 2011/2012 (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile).

10 Murray, HRRF, 232-233.

11 Murray, HRRF. 233.

12 Murray, HRRF, 231.

13 DH 1.1.

14 DH, 2.1.

15 DH 2.2.

16 See ST I, 1, 1.

17 See DH in Schindler, 382 ff.

18 ST, I, 93.

19 See Dulles, 28-30.

20 See HRRF 241 f.

21 See PRF 139 f.

22 Maritain, Man and the State, (University of Chicago, 1951), 160.

23 Seidentop, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism. (Harvard University Press, 2014).

24 Murray, “E pluribus unum: The American Consensus”, in We Hold These Truths (Sheed and Ward, 1960).

25 Maritain, 156.

26 Maritain, 158.

27Paul VI, Closing Message to Rulers. Abott, ed. The Documents of Vatican II (America Press, 1966) 730.

28 DH 13.1.

29 Maritain, 151.

30 Jn 10, 18.

31DH 13.1.

32ST, I, 1,1.

33 Maritain, 149.

34 See especially, Maritain, The Person and the Common Good (Notre Dame Press: 1973)