I gave the following lecture (really a series of meditations) on October 18, 2016 at the University of Notre Dame on the occasion of a Pastoral Symposium sponsored by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, designed to help bishops reflect and pray about the topic of «Reclaiming the Church for the Catholic Imagination». Bishops do not have many occasions to think aloud about the challenges the Church faces in our time. My thanks to Dr. John Cavadini and his associates at the McGrath Institute for Church Life for organizing this occasion.

+++

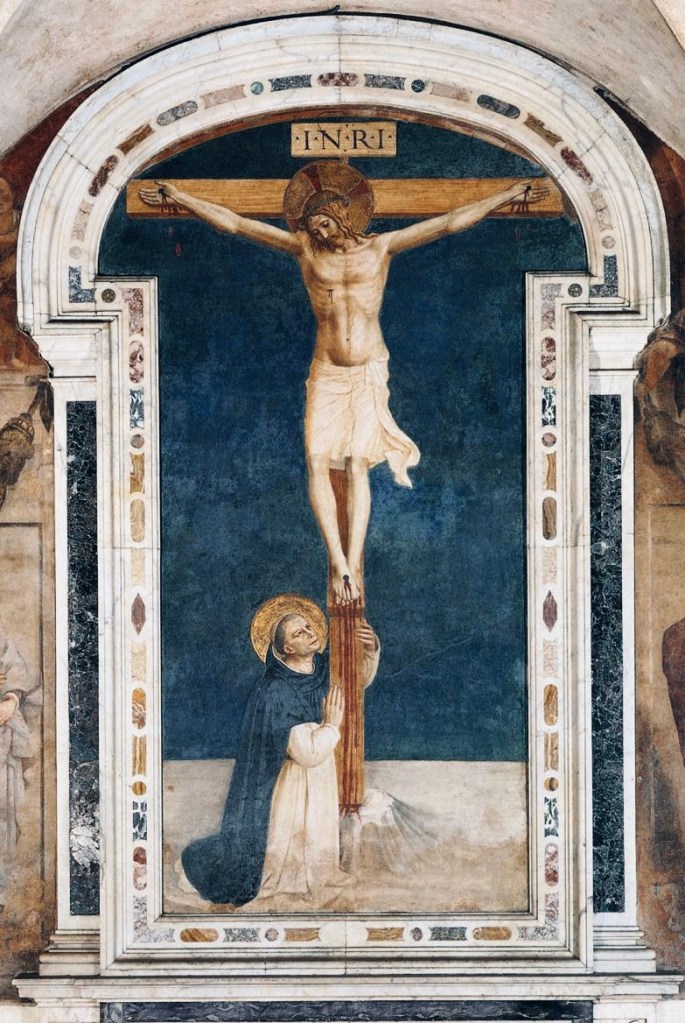

Fra Angelico, c. 1442, Convento di San Marco, Florence

Belonging to the Crucified: The Beauty of the Church in Image and Reality

To talk about the Church is dangerous for us. I mean, we are not the announcement, God the Most Holy Trinity, revealed in the act of saving us, is. The Father’s mercy offered us is in Christ Jesus and is made actual by the Spirit he pours out abundantly. As Saint Thomas, commenting on the poured out rivers of wisdom referenced in Ecclesiasticus 24, says beautifully in one place:

I understand these overflowing rivers to be the eternal processions, by which the Son from the Father, and the Holy Spirit from each, proceed in an ineffable way, […] Comes now the Son and the enclosed rivers in a certain way overflowed by his making known the name of the Trinity.(1)

Primarily the New Testament is the state of one who lives the grace of this Trinitarian overflowing. Only secondarily is it a series of books. The inspired texts are at the service of the renewing grace. The Son’s embrace of us, when accepted in faith, saves us by engendering the outpouring of the Holy Spirit who enacts the life, communion and mission of the Son in us.(2) The Spirit thus makes us instruments of the Kingdom’s coming even as he prepares a place for us in the Father’s Kingdom come to fullness.(3) To this renewal Saint Thomas bears theological witness and summarizes the Tradition East and West. This, too, is a kind of overflowing river.

The Church is the historical body constituted by this dynamic. She is endowed with gifts and graces that enhance her joy at being called into Trinitarian life, and that aim at advancing the universal call to the nations. Hence, though the Church is not the message, she is essential to the economy of salvation. She is not an afterthought. Yet, we have to grasp her beauty by a kind of side-ways glance. She is known in the act of her being. She is known in the act of imparting the Trinitarian participation, itself identical with what the Lord offers by saying:

This is the time of fulfillment. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and believe in the gospel (Mk1:15).

Part of what preoccupies us today is the difficulty we encounter in trying to convey to the generations entrusted to our care the beauty and joy of this life we have received. In large measure that is why we are dedicating these days to prayer and theological reflection. What I offer this evening is conceived as a side-ways glance; it is more a series of meditations than a lecture; more examination of conscience than prescription. If the examination of conscience part helps you, all the better, but I mostly aim that part at myself.

I. CONFIRMATION

We spend an awful lot of time as bishops confirming people in the faith, yet bishops and theologians talk and write very little about this pivotal moment and gift. It is the personal consummation of the Trinitarian enactment I just described; it is Pentecost applied, and thus the completion of the Paschal grace of the Risen Christ given to a Christian. It solidifies and missionizes our being in the Church. I speak to Confirmation candidates mostly about this gift as one that enables them to take up the mission of Jesus and thus bear witness to the Kingdom. By a kind of pastoral spontaneity, I find myself talking about this by describing how the Kingdom is decidedly different from what we encounter every day.

At some point in my confirmation homily I draw an explicit comparison between the Kingdom Jesus announced and ushered in– the very same Kingdom that the Spirit comes to make real in our lives– with the spirit of the world. I do not often call it the spirit of the world, since I am not sure 15 year olds know quite what to make of such a phrase. Instead, I talk about the obsession the world seems to have with power, money and control. For a while I used The Hunger Games to help them picture the point. Saying something like “life is not supposed to be The Hunger Games”. For the most part they have either read the books, or seen the movies, and so they tend to “get” that the fear that dominates the young people in those stories is not what Jesus and the Spirit, and the Church are about. I suspect they follow me in the Jesus and the Spirit part, but have not really thought of the Church as somehow connected to the offer of something that is described to them as “not The Hunger Games”. My pastoral gut tells me they do not react negatively to my drawing the Church into the vision I am trying to depict; rather, I suspect that they never really have pictured it before. In some sense, this may be what our conference over the next couple of days is about.

Quite by accident, if you believe in such things, during a confirmation last year, I didn’t say The Hunger Games, rather, I misspoke and said “life is not supposed to be The Game of Thrones”. The line drew a few giggles from the candidates, and a gasp from a parent or two. This made me think that the candidates knew exactly what I was talking about, and maybe their familiarity with it was not always with parents’ permission. But that is the world our families live in. Well, instead of correcting myself, I decided to run with the misspeaking, and mentioned that I have not watched the HBO series, though I have read the books. I made them laugh when I said: Do you know how hard it is to read a book and close your eyes at the same time? I mean, you know, there is some pretty ugly stuff in those books: ambition, treachery, murder, maiming, the good guys get beheaded, and the bad guys sit on thrones, and then they get beheaded; and those are in the happy parts.

Well, I have taken to using The Game of Thrones reference more regularly, since I think it makes the point as effectively as a reference to The Hunger Games. Teenagers and adults are fascinated by the gruesome display of how power, wealth and control swirl in dark configurations in this fictional world. It is both attractive and repulsive to them. Perhaps the popularity has to do with the fact that a great many people imagine that, once you take away the smoke and mirrors, the world actually operates this way. The popularity of dystopian fiction, which is never far from apocalyptic themes, should tell us something; and its popularity with the young is particularly significant. What is striking to me is that The Game of Thrones actually does hit the nail on the head with regard to saying something about the difference between what people experience and the Kingdom. This is of course my point in drawing the comparison.

The world tends to want to get rid of its problems, I tell the teenagers at Confirmation, and Jesus was a problem it tried to get rid of. He rose. This is the hope of the Church in the face of the ugly display of death’s cruel dance. The beauty of Christ risen in the flesh from the dead, though, is inherently difficult for us to picture or describe. I ask the candidates to witness to it by not letting life become a game of any kind. Christ is risen, and his victory is projected into the world by showing the fruit of his victory. This is the work of the Spirit. As Saint Athanasius said, a Christian’s ability to trample the menace of death is the sign of his rising; for a dead man cannot inspire such things.(4)

II. THE BEAUTIFUL AND THE UGLY

Saint Bonaventure, The Mind’s Road to God:

The mirror offered by the outside world is of little or no value, if the mirror of the mind be not made clear and polished. Train yourself, therefore, O man of God, by first heeding the biting sting of conscience before you lift up your eyes to the shining rays of wisdom reflected in those mirrors, lest from such radiant reflections you fall into a deeper darkness.(5)

There’s a lot of ugly stuff in the world, I tell the Confirmation candidates. I think when we draw peoples’ attention to this, be they teenagers or adults, they get what we are talking about. I think they get it more readily that way than if we say there is a lot of bad stuff, or if we say there are a lot of lies in the world. It is a risky strategy, because the apprehension of the beautiful has as much to do with the state of the soul as it does with the form of the object. Bonaventure says as much in the text I just cited. Still, I think we can trust the fact that human nature’s apprehensive capacities were not completely lost in the fall, nor washed away by the flood. People trust their gut more when it comes to the beautiful than they do when it comes to the good and the true. As Walker Percy might say, as a society we have surrendered judgments about the true and the good to the experts.(6) I do not think ordinary folks have yet similarly surrendered judgments about the beautiful. This is why I guess Walker Percy focused on story-telling. And certainly Tolkien trusted a great deal in a reader’s capacity to respond spontaneously to the noble and the beautiful.

It is the metaphysical irony of a fallen world, though, that it is easier to make the ugly fascinatingly attractive than it is to depict the beautiful as conducive to joy. This is a phenomenon at least partially operative in much dystopian fiction. It is also a phenomenon more easily observed than analyzed. In any case it may help account for the economic success of The Game of Thrones franchise.

The human being looks at an ugly world and begins to falter: maybe the ugly triumphs over our noble and beautiful dreams. As Pope Benedict put it: maybe the beautiful is the illusion, and the ugly is what is most real.(7) This uncertainty is a kind of darkness, perhaps the most obscure darkness possible. To abandon hope in the triumph of the beautiful over the ugly is another way to describe what we mean by the word «despair».

Hope requires the recognition of a good that can be obtained despite formidable obstacles. If the truth is that there is no way out of the triumph of the ugly, than there is no stomach for putting up a fight against it. The fear of the Nothing, like an aggressive entity, destroys hope. (7a) In the field of contemporary philosophy this is a contest fought on the terrain of the radical deconstruction of meaning. I need not go there now; it is enough to recognize its shadowy presence lurking in the background of pastoral aesthetics.

All of this would be a mildly inviting topic for academic discussion were it not for the fact that it is a life and death matter. I see it mostly in the young. The triumph of the ugly is an option a teenager learns about quickly. Gangs and a culture of violence are about power made glamorous. Drugs, alcohol and pornography are about an escape culture made to appear preferable to reality; and the drug and human trafficking trade is about a wealth culture that visualizes people only as buyers, sellers and commodities. The ugly will not triumph in the end, — he rose— but it can triumph in the soul of a young person to the extent that it can block out anything truly luminous. In that way it engenders despair, the soul’s submission to the triumph of the ugly.

A soul tutored in grace knows that beauty is not understood only under a physical aspect; but many people do not see it this way. As the Colombian writer William Ospina once said: when it comes time to show forth the world, art demands realism not reality.(8) With this phrase the poet wanted to say that art has a responsibility to point towards the marvelous in life, often present at the periphery of human perception, where the eye of the soul can perceive the noble present even in an ugly reality. An artist lives to point towards perceptible realities that exist at the periphery of what is physically expressive.

In its greatness the beautiful invites us to gaze on a truth pointed to by the image. Realism can trace and image something beyond the immediately sensed reality. Thus, for the Catholic imagination, the reality in our realm can be made to bear witness to the reality of another realm. Saint Bonaventure’s metaphysics of resemblance, intensely at work in The Mind’s Road to God, locates the ability to perceive these traces and images within the renewal of grace. For Bonaventure, Saint Francis is an icon of Christ precisely because he was pulled into total conformity and resemblance, even unto bearing the marks of the Crucified. I think, for example, we misread Pope Francis on the poor, and on creation, if we neglect the contemplative hermeneutic of graced resemblance and perception initiated in the Franciscan tradition, particularly in the theology of Bonaventure.

It is good to recall that before anything else, people bear the image and likeness. We are the first subjects capable of bearing the graced resemblance. And secondarily, because all artistic representations are uttered in some way by people, painting and music, preaching, poetry and other types of discourse can also participate in the hermeneutic of graced resemblance. From this perspective we understand better that announcing and contemplating the image of Christ and his Church is a concern that involves reflection upon the interplay between the ugly and the beautiful first in human beings, and then in all modes of human expression.

III. BEAUTY AT THE EDGES

Pope Benedict XVI, who knows a thing or two about the vision of Saint Bonaventure, speaking about two years before his election:

The one who believes in God, in the God who has manifested himself precisely in the altered countenance of Christ Crucified as the love that is faithful “to the end” (Jn 13,1), knows that beauty is truth and that truth is beauty, but in the suffering Christ he learns also that the beauty of the truth implies an offense, a sorrow and, yes, also the dark mystery of death, that can only be encountered in the acceptance of the sorrow, and not in its rejection.(9)

Pope Benedict, gathering up a tradition of Catholic reflection on beauty, points us to Christ Crucified. There are few examples of cruelty and ugliness that could be compared to crucifixion. The ugly exists; a Christian neither wants nor can deny this. But the image of the Crucified in human flesh invites us to perceive the reality that lies beneath the image, and that radiates a luminosity perceptible even in the midst of the cruelty of the Cross.

The Crucified invites us to contemplate the truth of love. And because God embraced the human being precisely when he accepted to suffer and die by what is ugliest in our condition, the Cross of Christ shows us that love transfigures. Charity specifies the image, gives it clarity and thus makes it capable of signifying beyond itself.(10)

Bruno Forte thus writes:

The Whole has made its home in the fragment because the relationship of love which constitutes it as purest beginning of all that is has now offered itself in the flesh: beauty is the arche of the Three, revealed in its highest form at the hour of the abandonment of the Cross, where the suffering of the crucified God opens the way into the depths of divine communion.(11)

Javier Sicilia, the Mexican poet/novelist/human rights activist, describes this mystery of the Whole of love made present in the limited, crucified fragment in more dramatic terms:

Do you know what amazes me about the Incarnation? I continued, that it is altogether contrary to the modern world: the presence of the infinite in the limits of the flesh, and the fight, the fight with no quarter, against the temptations of the devil’s excesses. You do not know, Eminence, how much I have meditated on the temptations in the desert. “Take up the power”, the devil told him; that power that gives the illusion of being able to disrupt and dominate everything. But he maintained himself in the limits of his own flesh, in his own poverty, in his own death, so poor, so miserable, so hard. Our age, nevertheless, showing a face of enormous kindness, has succumbed to those temptations. “They will be like gods, they will change the stones into bread, and they will dominate the world”… to such an age we have handed over the Christ, and we do not even realize it.(12)

This crucified love initiates the drama of the Kingdom; quite simply, the choice before the world is between the way of seeking power to overcome all limits, or the way of love shining in the beauty of the limited fragment: so poor, so miserable, so hard.

The beauty of the truth implies offense, Cardinal Ratzinger said. This is not far from what Pope Francis means when he talks about the imperative of the Church’s identification with the poor and relegated. The realism of the Cross, the element that causes offense, is the same vision that sees the embrace of the poor as not just part of the program of the Church, but the heart of her basic identity. It is her reality that is itself the beautiful image, beautiful in the manner of the altered countenance of Christ Crucified. This beauty gives offense. Christ Crucified and the poor are at the periphery of the soul’s perception precisely because they are at the periphery of the world’s stage.

Pope Francis says in Evangelii Gaudium 198:

This option for the poor, as Pope Benedict XVI taught, “is implicit in the Christological faith in that God that has made himself poor for us, so as to make us rich by his poverty”. That is why I want a poor Church for the poor.(13)

To embrace the world’s rejected is to embrace the way of beauty and to reject the way of power. As such, the Church refuses to separate the Crucified from the world’s poor. By the poor, I mean what I take Pope Francis to mean, namely all the “not-beautiful”, “not-useful”, “not-acceptable” persons the world summarily ignores, manipulates, ostracizes, uses and then throws away. Most dramatically, these are the ones whom the world seeks in order to sell their unborn or immigrant body-parts. The world eats its own, in a grotesque and hellish effort to live beyond its limits. The condition of the Crucified is the condition of the poor, the ones sold and used.

A Catholic imagination drags the periphery to the center, so as to make us able to perceive the truth that the center by itself eclipses. This implies offense to the world because in this way the Church lifts up what the world considers ugly and embraces it as beautiful. The saints know this by instinct of grace. The image of Mother Teresa, and all who are like her, holding a dying baby born in poverty is the image of the Church whose center is made beautiful by the embrace of the periphery.

To present the beauty of the Church in this way is both to offend the world and to unleash, so to speak, the grace that acts in prevenient fashion. This is the grace that insinuates itself in what is left of the natural apprehensive abilities of the human soul. Such images speak to the secular world more powerfully than we know, or than the world will publicly admit.

IV. CONTEMPLATION AND PERCEIVING THE KINGDOM

Pope Francis in Evangelium Gaudium, number 264:

The greatest motivation for communicating the Gospel is to contemplate it with love, to linger over its pages and to read it with the heart. If we approach it in this way, its beauty surprises us, and returns to captivate us over and over again. For this it is urgent to recover the contemplative spirit that permits us to rediscover each day that we are depositaries of a good that humanizes, and that helps to live a new life. There is nothing better to hand on to others.(14)

The Holy Father would have us contemplate the contours of the Gospel frequently, and allow ourselves to be captured anew by its beauty. It would be a mistake, though, to think of this kind of contemplation as a perceptive grace focused primarily on glimpsing the timeless element in it. It is true that Thomistic descriptions of the move from meditation to contemplation emphasize the move from the contingent to the necessary, the particular to the universal.(15) This has to do with the order of being, since the end of eternal contemplation is the standard by which lesser contemplations are measured.

Still, this theological truth must be seen in context of Thomas’ insistence that the mixed life is the highest form of life available to us; it is patterned after the form of the Lord’s own way of life, contemplative surely, but active also, and most of all accessible.(16) Glimpses of the timeless are ever present in the Gospel. The Iconic tradition of the East wondrously pulls us into this perception. But the eternal in the text is distorted for us unless we remember that our being pulled upward is simultaneous to eternity’s moving downward into our realm, in dramatic and apocalyptic fashion. Somehow it is necessary to capture in contemplative ways something of this drama as well, as it forms part of its essential beauty and power to attract.

The artistic tradition of the West has for some reason of providence dwelt on this depiction of the action in the Gospel. From Caravaggio’s Deposition to Flannery O’Connor showing us an abandoned soul in a puddle of water, wrapped in wire, it is the drama of the act that communicates. Such representations project what it looks like for us to act in likeness to the Lord.

The Kingdom Jesus announces is abrupt and not easily imagined. But He spared nothing to help us picture it. The parables are depictions of grace in motion. When you think about it, grace can only be conceived as a movement. And as with all movements, it has a beginning, a middle and an end. The parable of the Prodigal Son is all the more dramatic for our not being told what the older son will do after his Father’s pleading. The parables are infinitely nuanced, with that human nuance that escapes the learned and the clever (and many a scripture scholar), but which delights and instructs the crowds.

A preacher struggles to find the images that can convey something of the Kingdom’s grandeur, its majesty, its promise. The challenge is closely related to the theological aesthetic I have been talking about. For indeed, a great deal of the Lord’s preaching of the Kingdom centered on what lies at the edge of human perception.

In his announcement of the Kingdom, the image speaks more efficaciously than does the theological statement. In searching for a language to describe this mystery, I find myself either focusing upon what the Kingdom is not: The kingdom is not like The Game of Thrones. Or I find myself trying to derive similitudes that remain close in form to those used by the Lord himself: the Kingdom of God is like the Rio Grande River.

When outside my diocese, I am frequently asked: where exactly is Brownsville? I have taken to giving the same answer: Brownsville is there where the Río Grande River gives up its life in the Gulf of Mexico, yet is never exhausted. I like this description because it turns the mind to the great mystery at the center of the Kingdom announced by the Lord: If you would have life, you must lose it or give it over. Even nature reflects this mystery in the way the River first touches then gives itself to the Gulf. The Kingdom is like that. It is a stretching toward another that simultaneously is a pouring out and being full. In so many different ways, throughout his public preaching, the Lord spoke of this. The Kingdom comes to birth in the pouring out that fulfills, the self-emptying that like the grain of wheat, dies and bears much fruit.

Christian contemplation glimpses the self-emptying of the Son as the movement of a moment in time that by a sideways glance shows us eternity’s ceaseless pouring forth. Its beauty in time and in eternity is charity.

V. THE KINGDOM AS TRANSGRESSION

Thomas says somewhere in De Veritate:

Whatever our understanding conceives of God falls short of his representation; and thus what he is always remains hidden from us; and this is the highest knowledge of him which we can have in this life, that we know God to be above all that which we think of him.(17)

William Franke wrote a fine book entitled Dante and the Sense of Transgression. As he guides us through Dante, he champions a recovery of a patristic and medieval apophatic theology. I agree with what I understand of Franke’s argument, namely that our best response to contemporary philosophical attempts at the radical deconstruction of all meaning lies precisely within our own apophatic tradition.

Deconstruction is a movement that seeks to undermine meaning because it conceives of it as a pure construction of the mind; meaning, thus, is something like a human institution. At root, for the deconstructionist, meaning is idolatry, an aggressive kingdom that keeps its subjects under a controlled dominion. In that sense meaning is an extension of the power-play. The Game of Thrones, whether conceived so or not, is a parable of deconstruction.

Apophaticism recovers the Christian critique of meaning by relentlessly resisting its being idolized within the confines of the world. The wordiness of meaning is relative to and must find its way back to the One WORD from whom all words have any hope of sense; this is the One WORD we cannot conceive. From the Greek Fathers to Bonaventure, Thomas, John of the Cross and beyond, the not knowing, or the silencing of the words, is the vehicle of our sideways glance at the fullness of beauty and truth. To embrace the unsayable is to purify the legitimate meaning of the world. This is so because without a trace back to the source, meaning becomes idolatrous, and can become a tool in the money, power and control game that I tell confirmation candidates is not what the Kingdom is about.

Franke says the following:

The scattering and forgetting in question are transgressions and destructions of the entire regime of poetic representation and theological revelation of truth that subtend Dante’s poem and its intellectual and cultural tradition. It is through resolutely transgressing every order of presentation and representation that Dante finally delivers his divine vision. Most deeply understood, it is a non-vision –which, nevertheless, in its very forgetfulness casts a shadow of infinitely rich and nuanced images that are glimpsed in the act of disappearing.(18)

If Dante breathed the air of the theological tradition that kept guard over the unsayability of the Godhead, it is because the Tradition held fast to something present in the Lord’s own announcement of the Kingdom. There is a kind of transgression, a kind of subversion, and indeed a kind of deconstruction that is inbuilt in the Gospel announcement itself. Every positive description of the Kingdom is at the same time a negation of what the figure of the world proposes as normative. In this sense, the announcement of the Kingdom is inherently deconstructive. But again, in Christianity, deconstruction is a radical purification, not a demolition.

Every generation must come to grips with the subversive element in the Lord’s preaching, both in its form and in its content. We must become nimble with the way the Lord both proposes and negates in order to provoke a vision of the Kingdom. The Kingdom is not like the Rich Man’s table; it is like Lazarus’ vindication. The Kingdom is not like simply fulfilling the Law; it is like selling all you have and giving to the poor. The Kingdom is not like Pilate’s judgment seat; it is like Christ scourged and giving taciturn witness to the truth.

The Lord Jesus, in all of his parables, sayings, gestures and teachings tries tirelessly to help us glimpse a vision of the Kingdom. The urgency of this announcement is paramount: Foxes have lairs birds have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head. He has not come to build a cozy place of comfort; home is the act of bringing forth the Kingdom. Let the dead bury their dead, as if to say that the works that matter are for the sake of life. He does not come for the sake of making a better status quo where, in the end death demands our surrender. The Kingdom is not about the closed orb of the world where filial piety is the best nature can do to tame the unflinching specter of death. And he who puts his hand to the plow and looks back is not worthy of the kingdom. No, in the Kingdom if we see only what we leave behind, we will never glimpse the presence of the Kingdom that breaks through by means of the love that endures the Cross and triumphs over death.

And thus the announcement of the Kingdom is inherently apocalyptic, that is to say it is a break-in that opens up to the final breakthrough. I ask myself if my speaking about the Parousia is in proportion to the Lord’s speaking of it. As an Argentinian preacher I rather enjoy put it:

Forgetfulness of the Parousia—that powerful engine of all the religions that have ever been—sterilizes and confounds contemporary religion. Hope remains truncated. Man necessarily looks forward; and from now on there is nothing for humanity except horrors, which want to pacify us with the abstract and colorless idea of a “personal heaven, which for most people is unimaginable.(19)

This privatized comfort zone that passes for eternity these days is simply the closed-in world projecting a lifeless self-image into eternity. The Lord transgresses by offering something else, the apocalyptic communion of the Eternal Banquet. How do we invite to a banquet a world that would rather eat alone?

VI. WHY DO YOU SEEK THE LIVING AMONG THE DEAD?

Pope Benedict, writing about 15 years before his election, identified with characteristic succinctness an important aspect of the current situation faced by the Church:

For the great part of the people, the discontent with the Church has its origin in the fact that it is an institution like so many others, and as such, it limits my freedom. […] The anger against the Church or the disappointment that it provokes, have a specific character, because from her is expected, quietly, more than is expected from other mundane institutions.(20)

There exists a cultural resentment against the Church. The Church seen as an authority participates in the resentments that authorities, even good ones, can engender. And as an authority she is perceived as the institution among institutions.

Being an institution is not the problem, though, any more than meaning in the world is the problem. The problem is construing the institution or the meaning without reference to its original source. In the case of the Church, her form derives from the Kingdom of the WORD, just as in apophaticism, meaning is derivative and relative to the WORD beyond human speaking.

Once again, William Franke helps us.

Transcendence is realized in the world through the infinite critique and deconstruction of worldly powers. This is a vital truth of the Christian religion as rediscovered particularly in our time.(21)

Perhaps we have need to understand ourselves better as an institution that is inherently deconstructive, which is to say, prophetic and subversive in its critique of the powers of the world. The Church is an institution but she also participates in the Lord’s refusal to absolutize the order of the world. For some reason, people do not perceive that aspect of the Church’s life so clearly. There is something of Chesterton’s The Man who was Thursday in our position. Seen from behind, the figure of Sunday is brutish; seen from the front, angelic.

I take William Franke’s point to be not far from the terrain René Girard plowed when he argued that the Gospels are an unrelenting deconstruction of archaic religion and its sacrificial system.

Here indeed is the true difference between the mythic and the biblical. The mythical persists as a deception of the phenomena of the scapegoat. The biblical unveils its lie by revealing the innocence of the victims. If the abyss that separates the biblical from the mythic is not identified, it is because, under the influence of an old positivism, it is imagined that, for them to be really different, the texts should refer to different subject matters. In reality, the mythic and the biblical differ radically because the biblical breaks for the first time with the cultural lie par excellence, up until then hidden, of the phenomena of the scapegoat, upon which human culture was founded.(22)

Nothing brings to our people the subversive element that is the grace of the Kingdom than the Lord’s open accessibility to the poor, the strange and the outcast. In the Kingdom the world’s rejected are the favored. The sinners, the tax-collectors and the prostitutes will enter the Kingdom before you. In Girard’s lexicon, these are the scapegoats. The invited will not come because they no longer sense that it is a gift to be invited. The poor know, because they know what it is like to be left out. The lepers know because they live what it means to be shunned. The publicans know because they realize what it means to be judged unfit for the first pew.

Unless we are blind to the drama of the Gospel, it is pervasively clear that Jesus enjoyed the multitudes and they enjoyed him. Women could yell to him from the crowd: Blessed is the womb that bore you. And he could shout back: Blessed indeed is the one who hears the word of God and puts it into practice. The poor and outcast liked him and he like them. For all of our exegetical sophistication, sometimes I think we miss this most obvious of things in the Gospel: Jesus did not just love people, he also liked them, which in this world is perhaps the more remarkable feat.

Jesus’ love for the poor is God’s embrace of the outcast. And this love for the forgotten is manifestly the source of his critique of the established powers that governed their daily lives. Whitened sepulchers he called them, over which people walk unaware (Lk 11, 44). And in Matthew 23, 15, he says:

Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites. You are like whitewashed tombs, which appear beautiful on the outside, but inside are full of dead men’s bones and every kind of filth. Even so, on the outside you appear righteous, but inside you are filled with hypocrisy and evildoing.

He was publicly subversive, not for the sake of gaining popularity, but for the sake of engaging the greatest enemy of the Kingdom, namely the leaven of the Pharisees.

As the Argentinian preacher once said:

He personally reserved to himself the preaching of the commandment “love of God and neighbor”, and left the rest to his disciples. He came to do battle against all manner of vices, evils and sins; but he personally battled against pharisaism. He took it on himself.(23)

Have we become deaf to the dramatic conflict that unfolds in the Lord’s battle with externalized, hypocritical religious observance? Have we let the Lord’s promise of mercy eclipse the need we have to see his battle with the closed-in institutions of his time as precisely heaven’s brutal critique of earth’s perennial power-game? The pharisaical masquerade is the deadly game: it says some people are important and others aren’t; that some people deserve respect and others don’t; that some lives merit protection, and the rest are commodities. This battle was for him to the end; and he gave not an inch to the falsities that perpetuated all that was and is ugly in the world.

And the Argentinian preacher continues:

They contradicted him, of course; they denigrated him, calumniated him, accused and misconstrued him, persecuted him, spied on him, and publicly reprimanded him. And then, the serene speaker and magnificent poet raised himself up to full stature, and they saw that he was fully a man. He protested their accusations, responded to their reproaches, confounded their learned with scorching replies. And making the polemic livelier each time, against those enemies that could do what they willed against him, the Young Rabbi took on enormous proportion and magnificently faced them body to body, with curses and whips.(24)

We must ever seek a grace of purification to free us from this contagion, all the more necessary if we are to be equipped to critique the false masks that governments and gangs, economies and ideological colonialists use to justify discarding the voiceless.

VII. BELONGING TO THE CRUCIFIED

Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium:

The key criterion for authenticity which the Apostles indicated [to Saint Paul] was that he not forget the poor (cf Gal 2,10). This great criterion, so that the Pauline communities not let themselves be devoured by the individualist style of life of the pagans, has a great relevance in the present context, where there is a tendency to develop a new individualist paganism. The intrinsic beauty of the Gospel cannot always be adequately manifested by us, but there is a sign that must never be lacking: the option for the last ones, for those whom society rejects and throws away.(25)

Perhaps we complicate the Kingdom too much. It is as simple as reaching a hand to give comfort to another, an act of coming out of my splendid isolation in order to enact a communion of the living, itself a sign of the Kingdom. This is a work of the Spirit. We miss the most important part of the beauty of the works of mercy if we focus only on the good that it does for the one who suffers. For in the condition of the world, the one who resists to offer mercy suffers also; that one also is poor, perhaps the poorest of all. He or she suffers the wire-marks of isolation. Even were such a one to be dropped into heaven, the experience would be hell.

Saint Thomas, on why the Cross was necessary:

In the first place, man knows thereby how much God loves him, and is thereby stirred to love Him in return, and herein lies the perfection of human salvation; hence the Apostle says in Romans 5:8: «God commends His charity towards us; for when as yet we were sinners . . . Christ died for us»(26)

Salvation consists in the response to the Christ Crucified, gracefully perceived as the extreme giver of love. Thomas, following Paul, never disassociates the death of Christ from the work of the Spirit, gift of the Risen Christ, inciting us to a real sharing in the love there manifested on the Cross.(27)

Christ did not need to be embraced to save us; but we need to learn to embrace him to be saved. Salvation is what it has always been, our response to him, a spontaneous embrace that makes possible our belonging to him. The embrace becomes an image that truly signifies the reality of the Kingdom if it shows itself in the realism of the here and now. The efficacious response in the Spirit to Christ on the Cross is pictured for us in Matthew 25: 31-46: what you did for the least of mine, you did for me. Judgment for us will be about whether or not at eternity’s gate one of the world’s forgotten is willing to speak well of us. The poor, the misfits, the ones nobody would miss if they disappeared, they already belong to the Crucified. We cannot capture the center unless we go to that edge where the rejected dwell, where he is. It is beautiful there.

I give the last word to the Mexican poet:

Yes, Father, no one can be further away from God than that One who was made a curse for us. Yet despite this, underneath that horror, in the depth of that silence, the Trinitarian union resounds like two notes separated and melded at the same time, like a pure harmony. That One is the Logos, the Word through which all was made. When we have learned to listen to that silence we will grasp it in all its fathomless depth. Only those who persevere in love can hear it.(28)

+ + +

+df

(1) ll texts cited that are originally found in Latin or in Spanish were, for purposes of this lecture, translated by me. Scriptum super Sententiis, Prologus: Flumina ista intelligo fluxus aeternae processionis, qua filius a patre, et spiritus sanctus ab utroque, ineffabili modo procedit. Ista flumina olim occulta et quodammodo confusa erant, tum in similitudinibus creaturarum, tum etiam in aenigmatibus Scripturarum, ita ut vix aliqui sapientes Trinitatis mysterium fide tenerent. Venit filius Dei et inclusa flumina quodammodo effudit, nomen Trinitatis publicando, Matth. ult. 19: docete omnes gentes, baptizantes eos in nomine patris et filii et spiritus sancti. Unde Job 28, 2: profunda fluviorum scrutatus est et abscondita produxit in lucem.

(2) Summa Theologiae, III, q. 46, a. 3

(3) Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 106.

(4) Saint Athanasius, On the Incarnation, (Christian Classics, 2009, electronic format) no. 30: Dead men cannot take effective action; their power of influence on others lasts only till the grave. Deeds and actions that energize others belong only to the living. Well, then, look at the facts in this case. The Savior is working mightily among men, every day He is invisibly persuading numbers of people all over the world, both within and beyond the Greek-speaking world, to accept His faith and be obedient to His teaching. Can anyone, in face of this, still doubt that He has risen and lives, or rather that He is Himself the life?

(5) Itinerarium mentis ad Deum, Prologus, no. 4: Praeventus igitur divina gratia, humilibus et piis, compunctis et devotis, unctis oleo laetitiae et amatoribus divinae sapientiae et eius desiderio inflammatis, vacare volentibus ad Deum magnificandum, admirandum et etiam degustandum, specula- tiones subiectas propono, insinuans, quod parum aut nihil est speculum exterius propositum, nisi speculum mentis nostrae tersum fuerit et politum. Exerce igitur te, homo Dei, prius ad stimulum conscientiae remordentem, antequam oculos eleves ad radios sapientiae in eius speculis relucentes, ne forte ex ipsa radiorum speculatione in graviorem incidas foveam tenebrarum.

(6) See, Signposts in a Strange Land, (Picador USA, 1991): “Science, Language and Literature”.

(7) Ratzinger, “La Belleza”in La Belleza, La Iglesia (Ediciones Encuentro, 2006, electronic format): Hoy tiene mayor peso otra objeción: el mensaje de la belleza se pone completamente en duda a través del poder de la mentira, de la seducción, de la violencia, del mal. ¿Puede ser auténtica la belleza o al final no es más que una mera ilusión? La realidad, ¿no es en el fondo malvada? El miedo de que, al final, no sea el aguijón de lo bello lo que nos conduzca a la verdad, sino que la mentira, lo que es feo y vulgar constituyan la verdadera «realidad», ha angustiado a los hombres de todos los tiempos.

(7a) I refer to the film (1984, enigmatic in my memory) The NeverEnding Story (Die unendliche Geschichte) co-written and directed by Wolfgang Peterson based on the 1979 novel of the same name by Michael Ende.

(8) William Ospina, «García Márquez, los relatos y el cine» in EL dibujo de América Latina, (Literatura Random House, 2014, electronic format).

(9) Ratzinger, “La Belleza”: Quien cree en Dios, en el Dios que se ha manifestado precisamente en los semblantes alterados de Cristo crucificado como amor «hasta el fin» (Jn 13,1), sabe que la belleza es verdad y que la verdad es belleza, pero en Cristo sufriente aprende también que la belleza de la verdad implica ofensa, dolor y, sí, también el oscuro misterio de la muerte, que sólo se puede encontrar en la aceptación del dolor, y no en su rechazo.

(10) This is reflected, I think, in the order of Pope Benedict’s encyclicals on the theological virtues. He began with charity which is proposed as beautiful, then to hope (proximate to the good), and then faith, presenting itself as the way of truth. In the end the true and the good are contemplated and lived as beautiful, but the age calls for the luminosity of charity to lead us back toward the good and the true. It is in the environs of charity that the Spirit grants us joy, and so I think it is part of Pope Francis’ aim to extend the reflection of Pope Benedict on the beauty of the faith that operates in love, to the joy of this love lived out in the concrete circumstances of human life. Evangelii Gaudium is replete with references to the beauty and its attractive force, as is, obviously, Amoris Laetitia. Laudato Si is particularly directed toward recognizing the beauty of the gift of creation, and responding to the call of this gift to a kind of care and stewardship that is rooted in the truth.

(11) Bruno Forte, The Portal of Beauty, Towards a Theology of Aesthetics, (Eerdmans, 2008, electronic format), Chapter Two: “The Word of Beauty, Thomas Aquinas”.

(12) Javier Sicilia, La confesión: El diario de Esteban Martorus (Debolsillo, 2016, electronic format): Sabe qué me maravilla de la encarnación? —continué—, que es todo lo contrario del mundo moderno: la presencia del infinito en los límites de la carne, y la lucha, la lucha sin cuartel, contra las tentaciones de las desmesuras del diablo. No sabe cuánto he meditado en las tentaciones del desierto. ”‘ Asume el poder’, le decía el diablo; ese poder que da la ilusión de trastocar y dominar todo. Pero él se mantuvo en los límites de su propia carne, en su propia pobreza, en su propia muerte, tan pobre, tan miserable, tan dura. Nuestra época, sin embargo, bajo el rostro de una enorme bondad, ha sucumbido a esas tentaciones. ‘Serán como dioses, cambiarán las piedras en panes, dominarán el mundo’… A ella le hemos entregado a Cristo y no nos damos cuenta.

(13) Evangelii Gaudium, 198: Esta opción —enseñaba Benedicto XVI—«está implícita en la fe cristológica en aquel Dios que se ha hecho pobre por nosotros, para enriquecernos con su pobreza»[ 165]. Por eso quiero una Iglesia pobre para los pobres.» The reference to Pope Benedict is from Discurso en la Sesión Inaugural de la V Conferencia General del Episcopado Latinoamericano y del Caribe (13 May 2007).

(14) Evangelii Gaudium 264: La mejor motivación para decidirse a comunicar el Evangelio es contemplarlo con amor, es detenerse en sus páginas y leerlo con el corazón. Si lo abordamos de esa manera, su belleza nos asombra, vuelve a cautivarnos una y otra vez. Para eso urge recobrar un espíritu contemplativo, que nos permita redescubrir cada día que somos depositarios de un bien que humaniza, que ayuda a llevar una vida nueva. No hay nada mejor para transmitir a los demás.

(15) See Summa Theologiae II-II, q. 180, art 4.

(16) See Summa Theologiae IIIa, q. 40, and II-II, q. 182, a. 2.

(17) De veritate 2, i, ad 9m: Quidquid intellectus noster de Deo concipit, est deficiens a repraesentatione eius; et ideo quid est ipsius Dei semper nobis occultum remanet; et haec est summa cognitio quam de ipso in statu viae habere possumus, ut cognoscamus Deum esse supra omne id quod cogitamus de eo.

(18) William Franke, Dante and the Sense of Transgression, (Bloomsbury, 2013, electronic format), Ch 6.

(19) Leonardo Castellani, “Nietzsche” in in Cómo sobrevivir intelectalmente al siglo XXI (Libros Libres, Juan Manuel de Prada, ed, 2008, electronic format): El olvido de la Parusía -motor potente de todas las religiones que han sido- esteriliza y confunde la religión contemporánea. La esperanza queda trunca. El hombre mira necesariamente hacia adelante; y ahora adelante no hay nada para la Humanidad sino horrores, los cuales quieren zenzarnos nos con la idea abstracta y descolorida de un «Cielo personal» para la mayoría inimaginable.

(20) Ratzinger, “La Iglesia”: in La Belleza, La Iglesia (Ediciones Encuentro, 2006, electronic format): Para la mayor parte de la gente, el descontento frente a la Iglesia tiene su origen en que es una institución como tantas otras y que, como tal, limita mi libertad. […] La ira contra la Iglesia o la desilusión que provoca tienen un carácter específico, porque de ella se espera, calladamente, más de lo que se espera de otras instituciones mundanas.

(21) William Franke, Dante and the Sense of Transgression, Ch. 18.

(22) René Girard, El Sacrificio (Ediciones Encuentro: 2012, electronic format), cap. 3: He Aquí la verdadera diferencia entre lo mítico y lo bíblico. Lo mítico permanece como el engaño de los fenómenos de chivo expiatorio. Lo bíblico desvela su mentira al revelar la inocencia de las víctimas. Si no se identifica el abismo que separa lo bíblico de lo mítico es porque, bajo el influjo de un viejo positivismo, se imagina que, para ser realmente diferentes, los textos deben referirse a asuntos diferentes. En realidad, lo mítico y lo bíblico difieren radicalmente porque lo bíblico rompe por primera vez con la mentira cultural por excelencia, hasta entonces oculta, de los fenómenos de chivo expiatorio sobre los cuales se ha fundado la cultura humana.»

(23) Leonardo Castellani, “Sobre tres modos Católicos de ver la guerra Española” (1937) in Cómo sobrevivir intelectalmente al siglo XXI. Él personalmente se reservó la prédica del mandato: «Amor a Dios y al prójimo», y dejó los demás a sus discípulos. Vino a luchar contra todos los vicios, maldades y pecados; pero Él personalmente luchó contra el fariseísmo. Lo tomó por su cuenta.

(24) Leonardo Castellani, “Sobre tres modos”: Lo contradijeron, por supuesto; lo denigraron, calumniaron, acusaron, tergiversaron, persiguieron, espiaron, reprendieron. Y entonces el sereno recitador y magnífico poeta se irguió, y vieron que era todo un hombre. Recusó las acusaciones, respondió a los reproches, confundió a los sofisticantes con cinglantes réplicas. Y haciéndose la polémica más viva cada vez, con unos enemigos que contra él lo podían todo, se agigantó el joven Rabí magníficamente hasta el cuerpo a cuerpo, la imprecación y la fusta.

(25) Evangelii Gaudium 195: El criterio clave de autenticidad que le indicaron fue que no se olvidara de los pobres (cfr. Ga 2,10). Este gran criterio, para que las comunidades paulinas no se dejaran devorar por el estilo de vida individualista de los paganos, tiene una gran actualidad en el contexto presente, donde tiende a desarrollarse un nuevo paganismo individualista. La belleza misma del Evangelio no siempre puede ser adecuadamente manifestada por nosotros, pero hay un signo que no debe faltar jamás: la opción por los últimos, por aquellos que la sociedad descarta y desecha.

(26) Summa Theologiae, III, 46, 3, c.: Primo enim, per hoc homo cognoscit quantum Deus hominem diligat, et per hoc provocatur ad eum diligendum, in quo perfectio humanae salutis consistit. Unde apostolus dicit, Rom. V, commendat suam caritatem Deus in nobis, quoniam, cum inimici essemus, Christus pro nobis mortuus est.

(27) This is described in great textual detail in Saint Thomas’ commentary on Romans 5.

(28) Javier Sicilia, El díario: Sí, padre, nadie puede estar más lejos de Dios que aquel que ha sido hecho maldición. Y a pesar de eso, por debajo de ese horror, en el fondo de ese silencio, la unión trinitaria resuena como dos notas separadas y fundidas a la vez, como una armonía pura. Ése es el Logos, la Palabra por la que todo se hizo. Cuando hayamos aprendido a escuchar ese silencio lo asiremos en toda su insondable profundidad. Sólo quienes perseveran en el amor pueden escucharla.